Enter the Virtual Tour

INUA centres intergenerational knowledge and kinship, and highlights a long continuity of Inuit artistry and innovation both through the artworks and exhibition design. The exhibition is anchored by the informal architectures of the North, such as the hunting cabin, anaanatsiaq’s kitchen, or the ubiquitous shipping container, but also by intangible aspects of Inuit culture such as kakiniit, katajjaq, and unikaatuat.

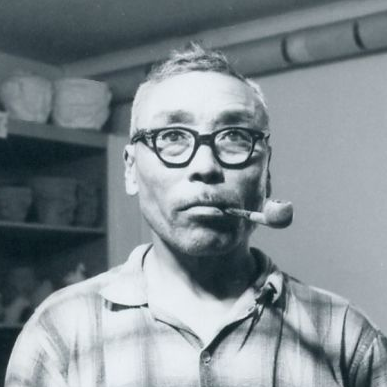

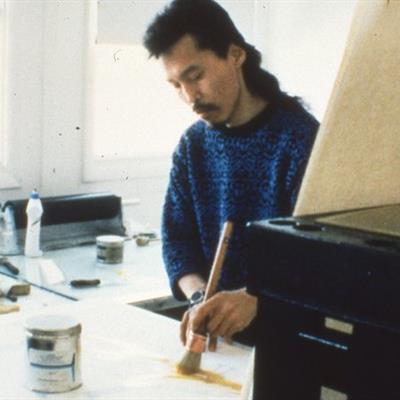

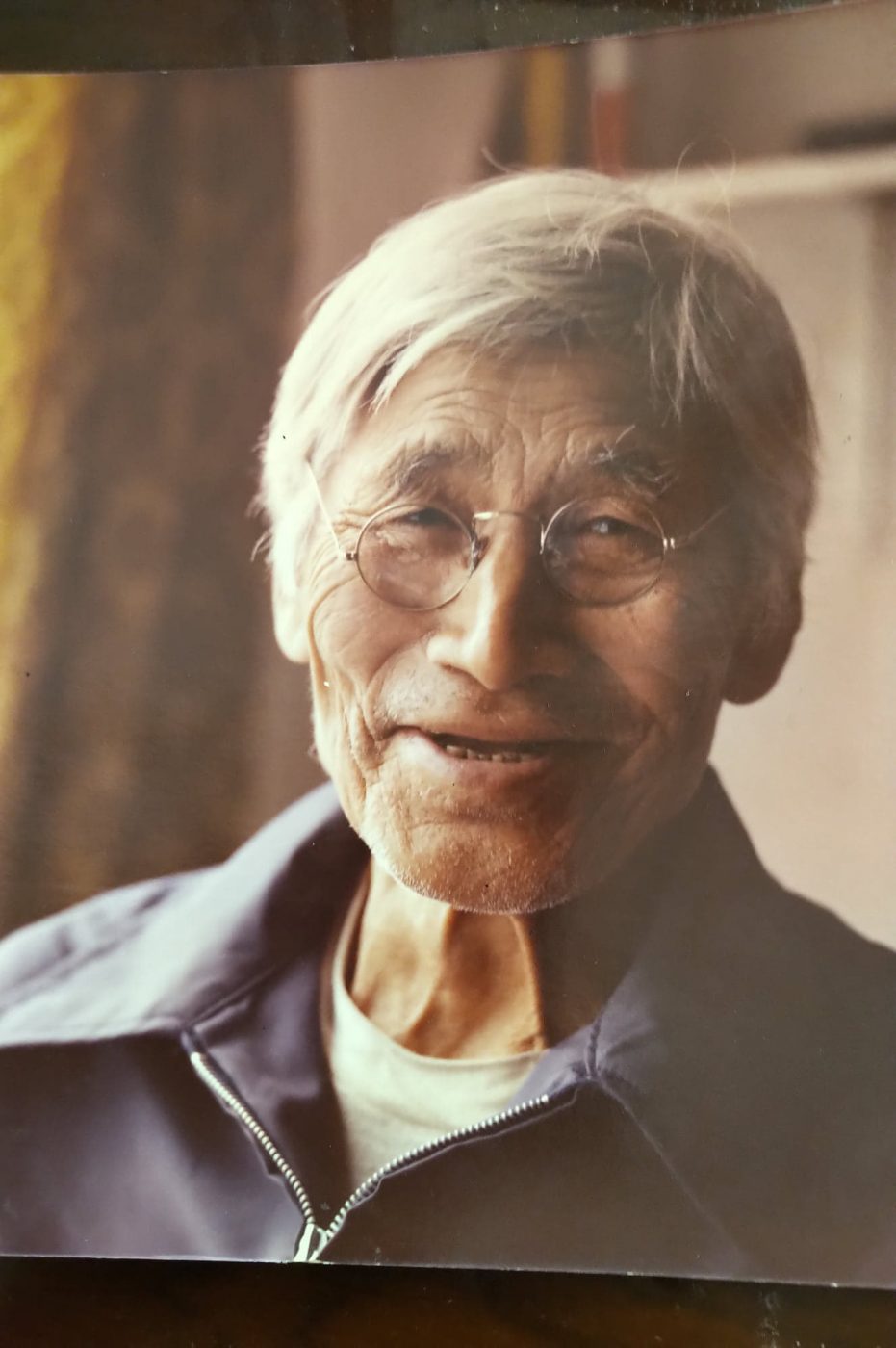

Maata (Martha) Kyak. Our Flourishing Culture. Photo by: David Lipnowski

Drawing attention to the changing seasons on the land and intersecting relationships between Inuit across Inuit Nunaat, the panels of Four Seasons of the Tundra are unique yet unified, much like the Alutiiq, Inughuit, Inuit, Inupiaq, Iñupiaq, Inuvialuit, Kalaallit, Yup’ik and other distinct groups of the Inuit family around the circumpolar Arctic. Likewise, the artists in INUA come from a diverse range of experiences and backgrounds, from emerging artists to Elders, who work across an equally broad range of media. The artists share their keen and cutting observations, wry Inuit humour and joyfulness, and perspectives on where we come from, and where we are going.

INUA is curated by four Inuit and Inuvialuit curators, representing the four regions of Inuit homelands in Canada today. From east to west, they are: Dr. Heather Igloliorte (Nunatsiavut); asinnajaq (Nunavik); Krista Ulujuk Zawadski (Nunavut) and Kablusiak (Inuvialuit Nunangit Sannaiqtuaq). It is also supported by many other Inuk contributors; Project Manager Jocelyn Piirainen; Exhibition Designer Nicole Luke; Graphic Designer Mark Bennett; Educator Kayla Bruce; and WAG Board Member & Indigenous Advisory Circle senior member, Theresie Tungilik.

INUA Online connects us to one another, and reveals artists, their works and contemporary Inuit thought. We invite you to revisit often as we continue to explore the works in the exhibition; share new stories and artist’s perspectives; and reflect upon our rich art history, dynamic futurity, and the continuity of our arts and cultures.

Media Sponsors

Content Partner

About Qaumajuq

Building on a long history of collecting and exhibiting Inuit art of all media at the WAG, Qaumajuq celebrates the largest public collection of contemporary Inuit art in the world. Qaumajuq’s inaugural show INUA is an important step in engaging in a meaningful and fulsome way with Inuit—artists, cultural workers, and people in general.

Maata (Martha) Kyak. Our Flourishing Culture. Photo by: David Lipnowski

ᐅᔾᔨᕈᓱᒃᑎᑦᑎᔪᖅ ᓄᓇᒥᑦ ᐅᑭᐅᑉ ᐃᓗᐊᓂᑦ ᐊᓯᐊᙳᖅᐸᓪᓕᐊᓂᖓᓂᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑲᑎᓐᓂᖏᑦ ᐱᓕᕆᖃᑎᒌᖕᓂᕆᔭᖏᑦ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᓄᓈᑦ, ᑲᑎᒪᔪᑦ ᓯᑕᒪᑦ ᐅᑭᐅᑉ ᐃᓗᐊᓃᑦᑐᑦ ᓯᓚᖓᑕ ᓄᓇᐅᑉ ᐊᔾᔨᐅᖏᑦᑑᔪᑦ ᑭᓯᐊᓂᓗ ᑲᑎᕐᒪᑉᓗᑎᒃ, ᓲᕐᓗ ᐊᓗᑏᖅ–ᑎᑐᑦ, ᐃᓄᒡᕼᐅᐃᑦ–ᑎᑐᑦ, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ–ᑎᑐᑦ, ᐃᓄᑉᐱᐊᖅ–ᑎᑐᑦ, ᐃᓅᐱᐊᖅ–ᑎᑐᑦ, ᐃᓄᕕᐊᓗᐃᑦ–ᑎᑐᑦ, ᔫᐱᒃ–ᑎᑐᑦ ᐊᓯᖏᓪᓗ ᖃᐅᔨᓐᓇᖅᑐᑦ ᐃᓅᖃᑎᒌᑦ ᐃᓅᑉᓗᑎᒃ ᖃᑕᙳᑎᒌᑎᑐᑦ ᐅᑭᐅᖅᑕᖅᑐᓗᒃᑖᒥᑦ. ᑕᐃᒪᓐᓇᑐᑦ, ᓴᓇᙳᐊᖅᑏᑦ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᓄᓇᖓᑦ ᐅᖓᒻᒧᐊᒃᑐᑦ ᐊᑕᐅᑎᒃᑯᑦ (INUA)-ᒥᑦ ᐊᔾᔨᒌᙱᑦᑐᓂᒃ ᐊᑐᖅᓯᒪᔭᖏᓐᓂᙶᖅᑐᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓇᑭᙶᕐᓂᖏᓐᓂᑦ, ᓴᓇᙳᐊᖅᑎᙳᖅᐸᓪᓕᐊᓂᕐᒥᑦ ᐃᓐᓇᕆᔭᐅᔪᓄᑦ, ᐱᓕᕆᖃᑦᑕᖅᑐᑦ ᑕᐃᒪᓐᓇᑐᑦᑕᐅᖅ ᐊᔾᔨᒌᙱᑦᑐᓂᑦ ᑕᑯᔭᒃᓴᐅᔪᓄᑦ. ᓴᓇᙳᐊᖅᑏᑦ ᑐᓂᐅᑎᖃᖅᑐᑦ ᐱᔪᒪᓂᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐱᑦᑕᐅᑦᑎᐊᖅᑐᓂᒃ ᖃᐅᔨᓯᒪᔭᖓᓐᓂᒃ, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐃᔪᕐᓇᖅᑑᑎᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᖁᕕᐊᓱᒃᑲᐅᓂᖏᓐᓂᒃ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑕᐅᑐᒐᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᓇᑭᙶᕐᓂᕆᔭᑉᑎᖕᓂᑦ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓇᒧᙵᐅᓂᑉᑎᖕᓄᑦ.

ᐃᓄᐊ (INUA) ᐋᖅᑭᒃᑕᐅᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᓯᑕᒪᓄᑦ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓄᕕᐊᓗᐃᑦ ᐋᖅᑭᒃᓱᐃᔨᓄᑦ, ᑭᒡᒐᖅᑐᐃᔪᑦ ᓯᑕᒪᐃᑦ ᐊᕕᒃᑐᖅᓯᒪᔪᓂᑦ ᐅᑉᓗᒥ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐊᖏᕐᕋᕆᔭᖏᓐᓂᑦ ᑲᓇᑕᒥᑦ. ᑲᓇᖕᓇᒥᑦ ᐱᖓᖕᓇᒧᑦ, ᐅᑯᐊᖑᔪᑦ: ᐃᖢᐊᖅᓴᐃᔨ ᕼᐃᐊᑐ ᐃᒡᓗᓕᐅᖅᑎ (ᓄᓇᑦᓯᐊᕗᑦ); ᐊᓯᓐᓇᔭᖅ (ᓄᓇᕕᒃ); ᑯᕆᔅᑕ ᐅᓗᔪᒃ ᓴᕚᑦᔅᑭ (ᓄᓇᕗᑦ) ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᖃᑉᓗᓯᐊᖅ (ᐃᓄᕕᐊᓗᐃᑦ ᓄᓇᖏᑦ ᓴᓐᓇᐃᖅᑐᐊᖅ). ᐃᑲᔪᖅᑕᐅᖕᒥᔪᖅ ᐊᒥᓱᓄᑦ ᐊᓯᖏᓐᓄᑦ ᐃᓄᖕᓄᑦ; ᐱᓕᕆᐊᕐᒧᑦ ᐊᐅᓚᑦᑎᔨ ᔮᔅᓕᓐ ᐲᕋᐃᓇᓐ; ᑕᑯᔭᒃᓴᖃᕐᕕᐅᑉ ᖃᓄᐃᖓᓂᐊᕐᓂᓕᕆᔨ ᓂᑳᓪ ᓘᒃ; ᐊᔾᔩᑦ ᖃᓄᐃᖓᓂᐊᕐᓂᓕᕆᔨ ᒫᒃ ᐱᐊᓂᑦ; ᐃᓕᓐᓂᐊᖅᑎᑦᑎᔨ ᑮᓚ ᐳᕉᔅ; ᐊᒻᒪᓗ WAG-ᑯᓐᓄᑦ ᑲᑎᒪᔨ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓄᓇᖃᖅᑳᖅᑐᑦ ᒥᒃᓵᓄᑦ ᐅᖃᐅᔾᔨᔨ ᐊᖓᔪᒃᖠᖅ, ᑎᕇᓯ ᑐᖏᓕᒃ.

ᐃᓄᐊ ᖃᕆᑕᐅᔭᒃᑯᑦ (INUA Online) ᑲᑎᑎᑦᑎᖃᑦᑕᖅᑐᖅ ᐊᑐᓂ ᐅᕙᑉᑎᖕᓄᑦ, ᖃᐅᔨᑎᑦᑎᑉᓗᓂᓗ ᓴᓇᙳᐊᖅᑎᒥᑦ, ᐱᓕᕆᐊᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐅᑉᓗᒥᐅᔪᖅ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐃᓱᒪᒋᔭᖏᓐᓂᑦ. ᖃᐃᖁᔭᑉᑎᒋᑦ ᑕᑯᔭᖅᑐᒃᑲᓐᓂᕐᓗᒋᑦ ᕿᓂᖅᓴᐃᖏᓐᓇᐅᔭᖅᑎᓪᓗᑕ ᖃᓄᐃᓕᐅᕐᓂᐊᓗᑕ ᑕᑯᔭᒃᓴᖃᕐᕕᖕᒥᑦ; ᐅᓂᑉᑳᓂᒃ ᑐᓂᓯᓗᓯ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓱᓇᙳᐊᖅᑏᑦ ᑕᐅᑐᒐᖏᓐᓂᒃ; ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐅᖃᐅᓯᕆᓗᒍ ᐱᑕᖃᐅᑦᑎᐊᖅᑐᖅ ᓴᓇᙳᐊᖅᑎᖁᑎᑐᖃᑉᑕ ᒥᒃᓵᓄᑦ, ᐊᔾᔨᒌᙱᑦᑐᓂᒃ ᓯᕗᓂᒃᓴᓕᕆᓂᕐᓂᑦ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑲᔪᓯᑎᓐᓂᐊᕐᓗᒋᑦ ᓴᓇᙳᐊᖅᑕᐅᔪᖁᑎᕗᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐱᖅᑯᓯᕗᑦ.

Media Sponsors

Content Partner

About Qaumajuq

Building on a long history of collecting and exhibiting Inuit art of all media at the WAG, Qaumajuq celebrates the largest public collection of contemporary Inuit art in the world. Qaumajuq’s inaugural show INUA is an important step in engaging in a meaningful and fulsome way with Inuit—artists, cultural workers, and people in general.

Nagvaaqtavut | What We Found: The INUA Audio Guide

Nagvaaqtavut | What We Found is a collaborative project that invites visitors to explore INUA – both in-person and virtually – by listening to diverse perspectives and reflections on the artworks in the exhibition, shared by Inuit from around the circumpolar world and across the country.

Created while in pandemic isolation, Nagvaaqtavut connects us across time and space to the artists and their works. Produced by the Inuit Futures in Arts Leadership: The Pilimmaksarniq / Pijariuqsarniq Project, Nagvaaqtavut shares the voices of numerous Inuit Futures Ilinniaqtuit (Inuit and Inuvialuit postsecondary students) as well as the curators, exhibition team, and artists, collaborating virtually. Together we share, examine, and explore creative ways of engaging with the artworks through sound, story, music, memory, laughter, language, and food.

Many thanks to the Nagvaaqtavut production team: Matthew Brulotte, Heather Igloliorte, Jean-Philippe Jullin, Tiffany Larter, Inuksuk Mackay, Tom Mcleod, Danielle Aimee Miles, Jasmine Sihra, and Dominic Thibault.

ᓇᒡᕚᖅᑕᕗᑦ (Nagvaaqtavut) ᐱᓕᕆᖃᑎᒌᖕᓂᒃᑯᑦ ᐱᓕᕆᐊᖑᔪᖅ ᑕᑯᔭᖅᑐᐃᖁᔨᔪᖅ ᐃᓄᐊ-ᒥᑦ – ᑕᒡᕙᐅᓗᑎᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᖃᕆᑕᐅᔭᒃᑯᑦ – ᑐᓵᓗᒋᑦ ᐊᔾᔨᒌᙱᑦᑐᑦ ᐊᒥᓱᐃᑦ ᑕᐅᑐᒐᐅᔪᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᖅᑲᐅᒪᒋᔭᐅᔪᑦ ᓴᓇᙳᐊᖅᑕᐅᔪᑦ ᒥᒃᓵᓄᑦ ᑕᑯᔭᖅᑐᖅᑕᐅᕝᕕᖕᒥᑦ, ᐃᓄᖕᓂᙶᖅᑐᑦ ᐅᑭᐅᖅᑕᖅᑐᓗᒃᑖᒥᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑲᓇᑕᓗᒃᑖᒥᑦ.

ᐋᖅᑭᒃᑕᐅᓚᐅᖅᑐᖅ ᓄᕙᒡᔪᐊᕐᓇᕐᒧᑦ ᐃᓄᑑᔭᕆᐊᖃᖅᑎᓪᓗᒋᑦ, ᓇᒡᕚᖅᑕᕗᑦ ᑲᑎᑎᑖᑎᒍᑦ ᐱᕕᖃᖅᑎᓪᓗᑕ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓂᖃᖅᑎᓪᓗᑕ ᓴᓇᙳᐊᖅᑎᓄᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐱᓕᕆᐊᕆᓯᒪᔭᖏᓐᓄᑦ. ᓴᖅᑭᑕᐅᔪᖅ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᓯᕗᓂᒃᓴᒥᑦ ᓴᓇᙳᐊᕐᓂᕐᒧᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓯᕗᓕᐅᖅᑏᑦ-ᑯᓐᓄᑦ: ᐱᓕᒻᒪᒃᓴᓂᖅ/ᐱᔭᕆᐅᖅᓴᕐᓂᖅ ᐱᓕᕆᐊᖅ, ᓇᒡᕚᖅᑕᕗᑦ ᑐᓂᓯᔪᖅ ᓂᐱᖏᓐᓂᑦ ᐊᒥᓱᑲᓪᓚᐃᑦ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᓯᕗᓂᒃᓴᖏᓐᓂᑦ ᐃᓕᓐᓂᐊᖅᑐᐃᑦ (ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓄᕕᐊᓗᐃᑦ ᓯᓚᑦᑐᖅᓴᕐᕕᒡᔪᐊᕐᒥᑦ ᐃᓕᓐᓂᐊᖅᑏᑦ) ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐋᖅᑭᒃᓱᐃᔩᑦ, ᑐᑯᔭᒃᓴᐅᑎᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᑦ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓴᓇᙳᐊᖅᑏᑦ, ᐊᑕᐅᑦᑎᒃᑯᑦ ᖃᕆᑕᐅᔭᒃᑯᑦ. ᐊᑕᐅᑦᑎᒃᑯᑦ ᑐᓂᐅᑎᖃᑦᑕᐅᑎᔪᒍᑦ, ᕿᒥᕐᕈᑉᓗᒋᑦ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᕿᓂᖅᓴᐃᑉᓗᑕ ᓴᖅᑭᑦᑎᓂᕐᒥᒃ ᐃᓚᐅᑎᑦᑎᓂᕐᒧᑦ ᓴᓇᙳᐊᒐᓕᐊᓂᒃ ᓂᐱᒃᑯᑦ, ᐅᓂᑉᑳᒃᑯᑦ, ᑎᑕᖕᓂᒃᑯᑦ, ᐃᖅᑲᐅᒪᓂᒃᑯᑦ, ᐃᒡᓚᕐᓂᒃᑯᑦ, ᐅᖃᐅᓯᒃᑯᑦ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓂᕿᑎᒍᑦ.

ᖁᔭᓐᓇᒦᑦᑎᐊᖅᑕᕗᑦ ᓇᒡᕚᖅᑕᕗᑦ– ᓕᐅᖅᑏᑦ: ᒫᑎᐅ ᐳᕈᓛᑎ, ᕼᐃᐊᑐ ᐃᒡᓗᓕᐅᖅᑎ, ᔮᓐ-ᐱᓕᐱ ᔪᓕᓐ, ᑎᕕᓂ ᓛᑐ, ᐃᓄᒃᓱᒃ ᒪᑲᐃ, ᑖᒻ ᒪᒃᓚᐅᑦ, ᑖᓂᐊᓪ ᐊᐃᒥ ᒪᐃᓕᔅ, ᔮᔅᒥᓐ ᓯᐅᕋ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑖᒥᓂᒃ ᑎᐴᓪᑦ.

Music: Seeder by Geronimo Inutiq featuring Taqralik Partridge.

Airplane

David Ruben PiqtoukunAirplane, 1995

Brazilian soapstone, African wonderstone.

Gift of Rosalie Seidelman., G-97-17 abc

Inuktut

Atiga Tom Mcleod, Umarramuitunga, Inuvialuk Aklavikmiutunga Inuvialuit Settlement regionmi.

Laughingwell Shingatuk nutaraat Bar-1mi, Jonas Meyook nutaraat Herschel Islandmi, Donald Gordon nutaraat Bar-2mi; tamaita aulayuaq tingmiyualukmun. Inuit, Western Arcticmi, itqaqtuat nutarakmun, tutqiktugaa tingmiyualuk aulaqtuat nangititchiyuat ilisakvikmun. Taamna tingmiyualuk nutaaq sivulliqmi. Mikiyuqmiq Inuvialuit tallimat manik $ niuvvaavikmi asiin inuuniarvik Aklavik tingmiyuaq sivikittuqmiq. Quliat taimaqtuat tadjvani, uqaqnaitut “ilisakvikmi” apiqsilaitut. Quliaqtuaq David Ruben Piqtoukun Tingmiyualuk, maqaigaa nutaraat Canadianmun governmentmi. Iglumun, taamna Iglu; iluani tingmaikpun tinginaiktuat.

Una savaatit itqaqsautit allauyuaq Angatkuqmun, atugaa taamna atiq allauyuaq niryunmiq tingmiyuaqlu. Asiin, itqaqsautit quliaq tapqua Ukpik-Arnaq.

Ingillaani Inuit angunaiqtut inuusim. Angulu arnaqlu uumayuat nuliaviik. Taamna angun angunaiqtut asiin arnaq Angatkuq. Asiin angun angunaiqtuat; arnaq kappiuqiyuaq uqqituaq atiq allauyuaq atugaa “pimagaalu” ilaksaqtuaq taamna ukpik. Taamna ukpik aulayuaq ui anguniaqtuaq asiin tumi iimayuk yaraiqsiqtuaq igliqmi. Asiin aulayuaq anguniaqti tukuyaa tuktu taamna akłak takuyaaluu, aglaan naluyuuq. Arnaq asulu ukpik takuyaa akłak asiin atugaa atiq allauyuaq akłak, nakłaaqtuaq uqaqtuaq uimun akłat nunami. Sukayuqtuaq pilaktuaq tuktu usiagaa qamotikmun asiin nuliaq kasuqtuat akłak taimaqtuqlu. Angun uutaqinaituq akłak kasuqtuat ilisimayuuq, sukayuq aulayuaq. Sukayuqtuaq nuliaqmun iglumi timi qitchugaalu kiiyaalu, ikimun tuquyuaq.

Una quliaq allauyuat arnaqmun niryunmun. David Ruben Piqtoukun Tingmiyualuk allauyuat. Aglaan angunmun isumamun asiin Inuit allauyuat.

English

Hello my name is Tom Mcleod I’m Umarramuit, Inuvialuk from Aklavik in the Inuvialuit Settlement region.

Laughingwell Shingatuk’s kids from Bar-1, Jonas Meyook’s kids from Herschel Island, Donald Gordon’s Kids from Bar-2; they were all picked up with the same Twin Otter airplane. People in the Western Arctic will reminisce about their youth, even about the order that they were picked up in the plane to be taken to residential school. As a plane ride was more of a novelty back then. Some Inuvialuit would even spend $5 at the trading post that would become Aklavik to fly for just a few minutes. But the stories stop there, no one will talk about what happened “at school” and no one will ever ask. This is the story depicted here by David Ruben Piqtoukun’s Airplane, the abduction of children by the Canadian government. From their homes, the Igloo; onto the airplane and away.

This artwork reminded me of a transformation like that of an Angatkuq, who could use their other names to transform into an animal and fly. Specifically, it reminded me of the story of Owl Woman.

A long time ago when Inuit hunted for their livings. A man and woman lived together as husband and wife. The man was a hunter and the woman was an Angatkuq. And when the man would go out hunting; the woman fearing for his safety would use another name she had “acquired” to become an owl. As the owl she would follow her husband on his hunting trips while her body stayed behind resting in her bed. On one such trip The Hunter had harvested a caribou which attracted a grizzly bear, unbeknownst to him. The Woman as an owl spotted the bear and used another of her names to become a bear, giving off a mighty roar letting her husband know that there were bears in the area. He quickened his pace butchering the caribou and loading it onto his sled while his wife fought the bear to a standstill. The man did not wait to watch the bears fight as he knew what was happening, so he left as quickly as possible. He rushed back to his wife at home to find her covered in scratches and bite marks, dying of her wounds.

This story is about the transformation of a woman to different animals. David Ruben Piqtoukun’s Airplane also depicts a form of transformation. But in this case not from man to spirit but from Inuit to something else.

Akia

Siku AlloolooAkia, 2019

sealskin on canvas

Collection of the artist

Inuktut

ᐊᑎᕋ ᓯᑯ ᐋᓗᓘ. ᐊᑭᐊ ᒪᒥᓴᕋᓱᐊᕐᓂ ᐊᔅᓱᕈᕈᑕᐅᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᖃᓪᓗᓈᑦ ᑎᑭᓐᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦ ᐊᕐᓇᐅᓪᓗᓂ. ᓴᓇᐅᒐᖅ ᐋᖅᑭᔅᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᓯᐊᑦᓇᒦᖔᖅᑐᓂ ᐃᒪᐅᑉ ᐃᖅᑲᖓᓄᑦ ᐊᓯᔾᔨᖅᑐᓂ ᓇᑉᐸᖓ ᓇᑦᑎᖅ. ᐊᓯᔾᔨᕐᓂᖓ ᐊᔅᓱᕈᖅᑐᓂ ᓴᖅᑭᖅᑎᑕᐅᓂᖓᓄ ᐱᑕᖃᑦᑎᐊᖅᑐᓂᑦ ᐱᑕᖃᖅᑎᑦᑎᔪᑦ ᐊᑭᖔᖓᓂ ᐃᐊᓗᐊᓃᑦᑐᑦ ᒥᑭᔫᑎᓂᑦ. ᐅᕙᖓ ᑎᑎᕋᖅᓯᒪᔭᖓᓂᑦ, ᐊᑦᑎᓪᓕᕙᓪᓕᐊᑎᓪᓗᑕ ᐊᐅᒻᒧᑦ ᐃᖅᑲᐅᒪᓇᖅᑐᒥ ᐊᒻᒪ ᐃᓕᕋᓇᖅᓵᕆᓗᒋᑦ ᐃᓚᒌᓄᑦ ᐅᓂᒃᑳᑦ, ᓴᖅᑭᖅᑎᑕᐅᓂᖓ ᐅᓂᒃᑳᖅ ᐱᒋᐊᖅᑎᑕᐅᔪᖅ ᑭᖑᒧᖔᖅ. ᑐᓴᐅᒪᔾᔪᑎᓕᕆᓂᖅ ᓇᑦᑏᑦ ᕿᓯᖏᑎᒍᑦ ᒪᑭᓴᕐᓗᒍ ᐃᓚᒋᔭᐅᖏᓐᓂᐅᔪᖅ ᐊᒻᒪ ᕿᓄᖓᓂᖅ ᐅᑯᓂᓄᖓ ᐸᓂᒃ, ᐊᑖᑕᖓ, ᐊᒻᒪ ᐊᖏᕋᖅ. 2,700 ᑎᑎᖅᑲᐃᑦ ᑐᓂᒐᓱᐊᖅᑕᒃᑲ ᐊᑭᖔᖓᓃᖔᖅᑐᑦ ᓂᕆᑎᓪᓗᒍ ᑕᕐᓂᖓ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ, ᐱᓗᐊᖅᑐᒥᑦ ᐊᓯᖏᑦ ᐅᕙᖓᑎᑐᑦ ᑕᒫᓂᑐᐃᓐᓈᖅᑑᔮᖅᑐᖅ ᐃᓚᒌᓂᑦ ᐊᒻᒪ ᓄᓇᖓᓂ ᐊᖏᕋᒥ. ᖁᔭᓐᓇᒦᒃ.

English

My name is Siku Allooloo. Akia is my attempt to heal what’s been suffered through colonialism as an arnaq. The artwork is set in Sedna’s descent to the bottom of the sea as she transforms into a half-seal goddess. Her transformation of suffering into the creation of bounty that provides from the other side is embedded throughout the piece. In my poem, as we descend into blood memory and an intimate family story, the creation story is activated in reverse. Communication through sealskin to heal disconnection and despair between a panik, her ataata, and home. The 2700 letters are my offering from the other side to feed the spirit of Inuit, especially others like me who find themselves displaced from family and homeland. Qujannamiik

Read Akia here: https://www.wag.ca/isl/uploads/2021/05/Akia-layout.pdf

The artist carved this poem out of sealskin as a layer of protection to hold the intimacy of the story. The fur obfuscates the clarity of the words and provides warmth within. The artwork was originally intended to be shown without a transcript.

Atii - Namesake

Maya Sialuk JacobsenAtii - Namesake, 2020

ink, acrylics, pencil on wood panels

Collection of the artist

Inuktut translation coming soon

Hello, this is Asinnajaq, a member of the Curatorial team. I am from Inukjuak, Nunavik and have spent most of my time in Tiohtià:ke also known as Montreal, Quebec.

Sialuk’s paintings have a special feeling of love and heart emitting from them. The bright colours and bold patterns really make this work stand out. but they are also paired with the soft warmth of the background of wood the work is made on. Atii focuses on the practise of naming. Names, which are more specifically spirit names in this context, connect those who have them to a legacy of family relation. When one has a name sake, they are placed in relationship immediately having life long connections to those around you. Being connected through names also means having duties to one another, like making sure that each other are safe and healthy, and giving when it’s needed. In this way Sialuk explaines to me “Also I see that as way to honor the title Inuit Nunangat Ungammuaktuk Atautikkut as we literally bring the old ways with us into the future and it is a significant identity marker for Inuit in Greenland.”

Birds & Bird Spirit

Marjorie Agluvak AqiggaaqBirds & Bird Spirit,

Inuktut

ᑯᔪᓚ ᒧᐊᕗᑦᖑᔪᖓ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐊᓈᓇᒐ ᐃᓅᔪᖅ ᑰᔾᔪᐊᕋᐱᖕᒥᐅᑕᖅ ᓄᓇᕕᒻᒥ.

ᐃᓅᓗᓂ ᐃᓱᕆᐊᒃᓴᖃᙱᑎᓪᓗᒍ ᕿᒥᕐᕈᐊᕆᐊᖅᑐᖅ ᓯᓚᒥ ᑎᒻᒥᐊᓂᒃ, ᐱᐅᒋᔭᕋ ᑖᓐᓇ ᓴᓇᓯᒪᔪᖅ! ᐱᙳᐊᖅᑐᑎᑐᑦ ᐃᑉᐱᓐᓇᖅᑐᓕᒃ ᖃᐅᔨᒪᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦ ᑲᓚᖏᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᖃᓄᐃᓕᖓᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦ ᓴᓇᓯᒪᔪᓄᑦ. ᐃᑉᐱᒋᔪᓐᓇᖅᑐᑎᑦ ᓄᓇᓕᖓᓂ ᐊᑐᖅᑕᐅᖃᑦᑕᖅᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦ ᐊᔪᕐᓇᙱᑦᑐᒃᑯᑦ. ᒪᔪᕆᐅᑉ ᓴᓇᙳᐊᒐᖏᑦ ᐅᖃᐅᓯᕆᔭᐅᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᐃᓱᒪᒃᓴᖅᓯᐅᕈᑕᐅᔪᑦ; ᑎᑎᕋᖅᓯᒪᓂᖏᑦ ᑕᑯᓐᓇᑦᓯᐊᙱᑦᑐᑦ ᐱᓪᓗᐊᕕᐅᔪᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓱᒪᒋᔭᐅᔪᒥᑦ. ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐅᓂᒃᑳᖏᑦ ᑕᑯᒃᓴᐅᒐᔪᒃᑐᑦ ᐊᓯᙳᖅᐸᓪᓕᐊᔪᓂᒃ − ᖃᓄᖅ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐊᓯᙳᕈᓐᓇᕐᓂᖏᑦ ᓂᕐᔪᑎᓄᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓂᕐᔪᑏᑦ ᐃᓄᖕᓄᑦ − ᐱᔾᔪᑎᓕᒃ ᑕᐃᑉᓱᒪᓂᖅ ᑕᒪᑉᑕ ᐊᔾᔨᒌᓚᐅᖅᑐᒍᑦ, ᐃᒡᓗᒥᐅᖃᑎᒌᒃᑐᑦ. ᑖᓐᓇ ᑎᑎᖅᑐᒐᖅ ᑎᒻᒥᐊᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐊᓂᕐᓃᑦ ᐃᖅᑲᐃᔾᔪᑎᖃᖅᑐᖅ ᐅᕙᒻᓄᑦ ᐅᖃᖅᑕᐅᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᐅᕈᓗᒥᑦ ᕌᔅᒥᐅᓴᓐᒧᑦ − “ᐱᔪᒪᐃᓐᓇᕋᔪᒃᑐᑎᑦ ᑖᒃᑯᐊ ᐊᓂᕐᓃᑦ ᑐᑭᖃᖁᑉᓗᒋᑦ ᑭᓯᐊᓂ ᐃᓱᒪᒋᙱᑕᕗᑦ ᑕᐃᒪᓐᓇ. ᖃᐅᔨᒪᔪᒍᑦ ᑐᑭᓯᐊᙱᓪᓗᒍ.”

English

I’m Kajola Morewood and my birth mother is Inuit from Kuujjuarapik in Nunavik.

As a person who spends their spare time going out in search of birds, I love this piece! There is a playfulness about it with the bright colours and the expressions of the figures. You can even get a sense of the regional clothing style even though it has been quite simplified. Marjorie’s work has been described as whimsical; blurring the lines between the real and the imagined. Inuit stories often feature transformation – how humans could transform into animals and animals into humans – referring to a time when we were all the same, living together. This depiction of birds and spirits reminds me of the quote by Orulo to Rasmussen – “you always want these supernatural things to make sense but we do not bother about that. We are content not to understand.”

Women's Torso

Oviloo TunnillieWomen's Torso, n.d.

stone

Winnipeg Art Gallery, Gift of the Canadian Museum of Inuit Art, 2017-589

Inuktut

“ᑲᕆᔅᑎᓐ ᕿᓪᓇᓯᖅ ᓗᔅᓯᕈᖑᕗᖓ, ᓴᓪᓗᐃᒻᒥᐅᑕᐅᕗᖓ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑲᑦᑐᓯᐅᑎᓯᒪᕗᖓ ᐅᑭᐅᖅᑕᖅᑐᒻᒥ ᓄᓇᓕᕋᓛᖑᓂᖅᓴᓄᑦ ᑰᔾᔪᐊᕌᐱᒃᒧᑦ”

ᑕᐅᒍᓐᓇᕋᑦᑕ ᓴᓇᙳᐋᒐᖅᑎᒍᑦ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐊᑐᖅᐸᓪᓕᐋᓱᖑᓂᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᐊᓯᕈᒃᐸᓪᓕᐋᓂᕐᒧᑦ. ᐅᕙᓂ, ᓱᕋᒃᓯᒪᓂᖅ ᐊᕐᓇᑐᐃᓐᓇᐅᒻᒪᑦ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑕᑯᒋᐊᑐᒐᑎᒍ ᒥᖅᓱᖃᑦᑕᖅᓯᒪᔭᖏᑦ, ᐊᒪᐅᑎᓕᐋᖓᓂ ᐅᕝᕙᓗᓂᑦ ᐊᑎᒋᓕᐋᖓᓂ ᓇᓗᓇᐃᖅᓯᒋᒍᑎᒋᒐᓱᐊᕐᓗᒍ “ᐃᓅᓂᖓᓂᒃ”. ᖃᐅᔨᒪᒐᒥ ᐱᖃᕆᐋᑐᖏᓐᓂᒻᒥᓂᒃ ᑭᓱᓕᕆᔾᔪᑎᓂᒃ ᐅᕝᕙᓗᓂᑦ ᐃᓕᖅᑯᓯᖃᕐᓂᒻᒥᓄᑦ ᐃᓕᓴᕐᓇᕈᑎᓂᒃ ᓇᓗᓇᐃᕈᑎᖓᓂᒃ ᐃᓅᓂᕐᒥᓂᒃ.

ᑖᓐᓇ ᓴᓇᙳᐋᒐᖅ ᐃᓕᓴᕆᒍᓐᓇᕋᒃᑯ ᐅᕙᖓ ᓇᒻᒥᓂᖅ ᐃᐱᒋᔭᓐᓄᑦ. ᐃᓱᒪᒍᑎᒋᓕᕋᒃᑯᑦ ᐅᕙᖓ ᐃᓗᐋᓂ ᑐᑭᓯᐋᓂᕆᔭᓐᓂ ᑎᒥᓐᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓇᒻᒥᓂᖅ ᐃᑉᐱᒋᔭᓐᓂᒃ ᐅᕙᖓᐅᓪᓗᖓ ᐊᓐᓇᐅᓂᓐᓄᑦ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐱᓗᐊᙳᐊᖅᑐᒥᒃ ᐃᓅᓪᓗᖓ ᐊᕐᓇᐅᓂᓐᓂᒃ. ᐅᑭᐅᖅᑕᖅᑐᒻᒧᐋᕋᖓᒪ, ᐊᔾᔨᐅᖏᑦᑐᒥᒃ ᐃᓱᒪᖅᓱᕐᓂᖃᓕᓱᖑᒐᒪ ᑕᑯᔭᐅᒍᓐᓇᓐᓂᕐᓂ ᐱᖓᓐᓇᒥᐅᑕᐅᓇᖓ ᐱᓕᕆᒍᑕᐅᖏᓐᓇᖃᑦᑕᓱᑐᑦ ᓂᕆᐅᒍᑎᒋᓇᒍᑦ ᐱᐅᓂᐊᓗᒻᒥᒃ. ᓱᖁᑕᐅᖏᒪᑦ ᖃᓄᐃᑦᑐᓂᒃ ᐊᑐᕋᓗᐋᕈᒪ, ᖁᐃᑦᑎᑲᓪᓚᓐᓂᕋᓗᐋᕈᒪ, ᐅᕝᕙᓗᓂᑦ ᐃᓱᒪᓕᐅᕐᓂᕋᓗᐊᕈᒪ ᐱᐅᓴᐅᑎᓕᕐᓂᐊᖏᓪᓗᖓ. ᐃᒫᖓᕐᓕ, ᐊᑐᖅᓯᒪᔭᓐᓂ ᒪᑯᐊᖑᒪᑕ ᐊᒃᑐᐋᖃᑎᒌᓐᓂᒃᑲ ᐃᓚᓐᓄᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓄᓇᓕᓐᓂᒥᐅᑕᓐᓄᑦ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓄᓇᒧᑦ. ᑕᐃᒪᓕ ᓂᐅᑐᐊᕋᒪ ᑎᒻᒥᓲᒥᒃ ᑎᐅᑎᐊ Tio’tià:ke (ᒪᓐᑐᕆᐊᒥ, ᑕᐅᕙᓂ), ᐃᑉᐱᒍᓱᓕᑦᑕᐅᑎᒋᓱᖑᔪᖓ ᐊᓯᐅᔪᔮᕐᓗᖓ ᐊᒃᑐᐊᒍᓐᓃᖅᑐᖓ ᓄᓇᒧᑦ. ᑐᕌᖓᒍᓐᓃᒻᒪᓪᓗ ᑕᒪᒃᑯᓄᖓ ᐊᒃᑐᐃᓂᕆᕙᒃᑕᓐᓄᑦ, ᑭᓯᐊᓂ ᐱᐅᓂᖃᓐᓂᒻᒨᖓᓗᐊᙳᐋᕐᒪᑦ – ᑐᕌᖓᖁᔨᓕᓪᓗᖓ ᑕᐃᒃᑯᓄᖓᓪᓗᐊᖅ ᓂᕆᐅᒋᔭᐅᒍᑎᓄᑦ.

ᐃᓗᒃᑯᑦ ᓇᒧᖓᖅᐸᓪᓕᐋᓂᕋ ᐃᓚᖃᖃᓯᐅᔾᔨᒪᑦ ᐃᓚᓕᐅᑎᒃᑲᓐᓂᓕᓐᓂᒻᒧᑦ ᐃᓚᓐᓄᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓄᓇᓕᒻᒧᑦ ᓄᓇᕕᒻᒥ, ᑕᒫᓂᓗ ᖃᐅᔨᕙᓪᓕᐋᓕᓚᐅᕋᒪ ᐃᑉᐱᒋᔭᓐᓂᒃ ᑭᓇᐅᓂᓐᓂᒃ ᐃᓅᓂᓐᓂᒃ ᐊᕐᓇᐅᓪᓗᖓ ᓱᓕᔪᕿᑦᑎᐋᕐᓗᖓ, ᖃᓄᑐᐃᓐᓇᐅᒐᓗᐋᖅᐸᑦ ᑕᑯᔭᐅᑎᓪᓗᖓ ᐅᕙᓐᓂᒃ. ᐃᓐᓇᕈᕋᑖᑦᑎᓪᓗᖓ ᓇᒃᓴᓚᐅᕋᒪᑦ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐃᓕᖅᑯᓯᖃᓐᓂᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᑕᑯᒃᓴᐅᑎᑦᑎᒍᑎᓂᒃ – ᓄᐊᑦᑎᓚᐅᖅᓯᒪᓐᓂᕋᒪ ᐊᓯᓱᐋᓗᓐᓂᒃ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐊᓐᓄᕌᖏᓐᓂᒃ, ᐱᓕᕆᔾᔪᑎᖏᓐᓂᒃ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐊᒥᐋᖅᑎᑕᒐᓐᓂᒃ ᐃᓕᒍᑎᒋᒍᒪᓪᓗᒋᑦ ᖃᐅᔨᒪᒍᑎᒋᒍᒪᓪᓗᒋᑦ ᐃᓕᖁᓯᖃᖃᑕᐅᓂᓐᓂᒃ ᑕᒪᑐᒧᖓᓗ ᐃᑉᐱᒍᓱᓪᓗᖓ ᐊᔪᖏᑦᑐᐋᓘᓂᕐᒥᒃ. ᑭᓯᐊᓂ, ᒫᓐᓇᐅᓕᖅᑐᖅ ᐊᓂᒍᓐᓇᖅᓯᒐᒪ ᓄᓇᕐᔪᐋᒧᑦ ᓂᕈᐋᕐᓗᖓ ᐊᑐᕐᓂᐋᖅᑕᓂᒃ ᐱᒐᓚᖏᓪᓗᓂ ᐱᐅᔪᐋᓗᒻᒥᒃ ᐊᖏᔪᖅᑕᖅᓯᒪᓗᖓ, ᑭᒻᒥᑯᑖᖃᓪᓗᖓ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑕᒪᒃᑯᐋᖑᓪᓚᕆᖏᒃᑲᓗᐋᕐᓗᑎᒃ ᖃᓄᐃᑦᑐᑐᐃᓐᓇᐃᑦ ᐃᓕᖅᑯᓯᖃᓂᕐᒨᖓᔪᑦ ᐃᑉᐱᒍᓱᒍᑎᒋᒐᓱᐋᓪᓗᒋᑦ ᐊᔪᖏᑦᑐᐋᓘᓂᕐᒥᒃ ᐃᓅᓐᓂᓐᓄᑦ. ᑕᒪᓐᓇᐅᐸᓗᐊᖅᑎᓪᓗᒍ ᖃᐅᔨᒪᒐᒪ ᖃᓄᖅ ᑎᒥᒐ ᑕᐅᑐᒃᑕᐅᓂᖓᓂ ᑕᒪᓂ ᑎᐅᑎᐊ Tio’tià:ke, ᐋᖅᑭᒍᑎᓯᒪᓕᕋᒪ ᐱᓇᓱᐋᕈᓐᓃᓪᓗᖓ ᓯᓚᑎᑯᑦ ᓇᓗᓇᐃᖅᑕᐅᒍᑎᒥᒃ. ᐃᓅᒐᒪ ᖃᓅᒐᓗᐊᖅᐸᑦ ᐅᕝᕙᓗᓂᑦ ᓇᒦᒃᑲᓗᐋᕈᒪ ᑕᕝᕙᐅᓗᖓ.

English

“I’m Christine Qillasiq Lussier, my ties are to Salluit, and I am affiliated to the Northern Village of Kuujjuaraapik”

We can see through carvings that Inuit are responsive to change. Here, the bust is simply a woman, and we do not need to see her sewing, in an amautik or an atigik to identify her as “Inuk”. She knows that she does not need any accessories nor any cultural markers to signify that she is an Inuk.

This carving resonates with my own sense of self. It makes me think of my inner journey of understanding my own body and my own sense of self as a woman, and specifically as an Inuk woman. When I go up north, I have a certain freedom in presenting myself without western conventional expectations of beauty. It doesn’t matter what I wear, if I put on some weight, or if I decide not to put on makeup. Rather, my experience is about the connections I have with family and community members, and the land. As soon as I get off the plane in Tio’tià:ke (Montreal, that is), I feel like I immediately lose that connection with the land. The focus is no longer on these connections, but on mere aesthetics- where my body is ascribed certain expectations.

My inner journey also included reconnecting with my family and community in Nunavik, where I began to experience my sense of identity as an Inuk woman in a confident way, regardless of how I present myself. In my early adulthood I bought many Inuit cultural markers- I accumulated a lot of Inuit clothing, accessories, and prints to learn to experience my culture in a way that felt empowering. But, I can now go out into the world choosing to wear simply a fabulous dress, high heels, and not necessarily anything cultural in order to feel empowered as an Inuk. Although I am aware of how my body is perceived in Tio’tià:ke, I have adjusted to not seeking external validation. I am an Inuk regardless of how or where I happen to exist.

Iluani/Silami (It's Full of Stars)

Glenn GearIluani/Silami (It's Full of Stars), 2021

shipping container, paint on plywood, sound and video projection

Collection of the artist

Inuktut

Aik, Atiga Glenn Gear ammalu una inigijaga, Iluani/Silami (tatajuk ullugianut).

Pisimavunga akulligejunut Inuit sivullivininginnit. Atâtaga Inuk Atlatok kangitlunganit Nunatsiavummi, (Taggami Labrador), ammalu anânaga Newfalâmiutak pisimatluni Irish-imit ammalu Kallunânit piusituKammit. Pigutsatausimavunga Corner Brook Newfalâmi ammalu iniKavunga Mânnaluatsiak Montreal-imi.

Iluani/Silami allasânguttitaugami imailingajuk Inside/Outside Kallunâtitut ammalu taijaujumut, “Ullugianik tatajuk” isumagillugu Kubrick-iup taggajânga, “2001: A Space Odyssey”.

Tânna ininga âkKisuttausimajuk iluani 20-foot takinilimmik umiakkut atuttauKattajumut itlivitsuamik upvalu imammiutak itlivialuk. Taikkua imammiutait itlivialuit Kaujimajautsiatut unuttumaginnik Inuit nunagijanginni atuttauKattamata atjatugiamut piKutinik ammalu sunatuinnanik pisimajunit siKinganimmit. Iluani, angijualuk Kinnitak ammalu KaKuttak allanguattausimajuk pingasunut Kammanut, sakKititsijumik maggonik atjiKangitunik takutsaujunik. Omajuit ammalu omajut-inunnik allanguattaumajut ilijaumajut satjugiangani tikijunut KakKasuanut tamâget atatlutik iluani KikKangani angijualuk ijik iluani taggajâk pisimajuk.

Itigavit, saumiani takugatsaKavuk ilinganiKajumut Inuit uKausituKanga Nunatsiavummit uKajumik Kanuk atsanet sakKiluasiasimammangâmmik. Atautsik unikkausik uKajuk sangijualumik inutuKak upvalu angakKuk tikisimajumut Kaummatluni nunamosimajuk. Sangijumik naulamminik nunatsuamottisijuk ammalu taimâk pigami, nalautsijuk ujagamik Killânikittutalik ammalu aniajaniatlutik atsanet iluanettunik, sakkutaujunut unnusami silamut atsaniunialittunut. Talippiani, takugatsaKavuk isumajâgutaujumik Inuit ininganik sivunittinenguajumut attutaumajumut Sonâbendimi ullâgatsukut cartooninguanik sollu taikkuninga ‘The Jetsons’. PitaKagivuk Kimmimik pottakajumik ammalu ânnigekkutimmik niaKunganik aullakallagasuattumut, kajusijumut angijumut ilannâga Jesse Tungilik ammalu Kisijammut Silamut Anugânga” takusauKataummijuk.

Tamakkua takutsaujuk atunik ammalu ukkuangani ilagiatsijuk akulligiallanik sanajaumajumut, saumiani pitaKatluni Inuit pitanginnik, Tuttuk, the caribou, (Kaujimajaummijuk Ingusialuk), ammalu talippiani pitaKatluni Ullaktut, The Runners (Kaujimajaummijuk pingasut Kaumatsiatut ullugiat iluani Orion-iup tatsiangani).

Tânna aumaluak takutsak iluani ijiup âkKitausimajuk nipanganut ingiulet apujunut Kilautammut, apvitatluni nipiliuttausimajut tânna sanasimajaga. Tânna takutsait suliangujuk âkKisuttausimajut malitsiagiamut Kilautammik, asianokatajonnut akunga piusilluasianganik ammalu tamânelluasiajumut sanasimajakkanik, taggajâliusimajakkanik, ammalu takutitsijuk âkKisuttausimajunik Kilautait, asiangutitsijumik pitagijanginnik ammalu tamânelluasiajunik sanasimajakkanik, taggajâliusimajakkanik, nipiliusimajakkanik inigganiagama Labradorimut fifteenait jâret Kângisimajunik.

Tamakkua ullugiat iniuvuk isumakkut Kaujimajaungituk Kaummalâjut, nipaKainnatumik, ammalu atjiKangitunik takutsait. Iluani/Silami iniuvuk asiKangitumik iniuvuk iniKattitaujumillu sivunganiusimajumik, ammalu sivunittinik; itlivialuk tigumiajumik nalligijakkanik Labradorimik atajutigut unikkausivininnik, nunatsuamut, imappimut, ammalu ullugianut.

English

Iluani/Silami (it’s full of stars)

Hi, my name is Glenn Gear and this is my installation, Iluani/Silami (it’s full of stars).

I come from mixed Inuit ancestry. My father is Inuk from Adlatok Bay, Nunatsiavut, (Northern Labrador), and my mother is a Newfoundland settler with Irish and English heritage. I grew up in Corner Brook Newfoundland and I currently live in Montreal.

Iluani/Silami translates as “Inside/Outside” in Inuktitut and the subtitle, “it’s full of stars” is a reference to Kubrick’s film, “2001: A Space Odyssey”.

The installation is set inside a 20-foot long shipping container or sea can. These sea cans are familiar in many Inuit communities as they are used to ship goods and supplies from the south. Inside, a large black and white mural wraps around the three walls, creating two distinct scenes. Animals and animal-human hybrids are set against a coastline that stretches into the mountains with both sides connected in the middle by a large stylized eye into which a video is projected.

As you enter, on the left there is a scene depicting an Inuit origin myth from Nunatsiavut of how the northern lights came to be. One such story tells of a powerful elder or shaman who came across a shimmering in the ground. He thrust his spear into the earth and when he did, he struck the rock labradorite and freed the aksaniq within, releasing them into the night sky to become the northern lights. On the right, there is a scene depicting an imagined Inuit village of the future inspired by Saturday morning cartoons such as ‘The Jetsons’. There is a husky with a jetpack and a bubble helmet about to blast off, a direct nod to my friend Jesse Tungilik and his “Sealskin Spacesuit”, also in the show.

The constellations depicted in each scene and on the doors add another layer to the piece, the left side containing the Inuit constellation, Tukturjuit, the Caribou, also known as the Big Dipper, and the right side containing Ullaktut, The Runners, also known as the three bright stars in Orion’s Belt.

The circular projection in the eye is set to the sound of crashing waves with a rhythmic drum beat, field recordings I made for this piece. The scenes projected are edited to the beat of the drum, alternating between fractal forms and live-action sequences I made, filmed, and recorded during my travels to Labrador over the past fifteen years.

This installation is a space of meditation with its mysterious flickering light, rhythmic sound, and panoramic visuals. Iluani/Silami is a portal to a magic place of overlapping time of past present, and future; a container that holds some of my love of Labrador through a connection to its legends, land, sea, and stars.

My Little Corner of Canada

Zacharias KunukMy Little Corner of Canada, 2020

four-channel video installation

Collection of the artist. Commissioned with funds from the Mauro Family Foundation.

Inuktut

ᑯᕆᔅᑕ ᐅᓗᔪᒃ ᔭᕗᐊᑦᓯᑭᐅᕗᖓ ᐃᒡᓗᓕᒑᕐᒥᐅᑕᐅᔪᖓ ᐊᒻᒪ ᑲᖏᖅᖠᓂᕐᒥ, ᓄᓇᕗᑦ. ᐃᓚᒋᔭᐅᔪᖓ ᐊᐅᓚᑦᑎᔨᐅᔪᓂᒃ ᐆᒥᖓ ᐃᓄᐊ.

ᐃᒡᓗᕋᓛᖅ ᑕᕐᕆᔭᓕᐊᖑᔪᓂ ᐃᓱᒪᒃᑯᓐᓂ ᑲᒪᓇᖅᖢᓂ ᐊᒻᒪ ᑲᒪᓇᕐᔪᐊᖅᖢᓂ ᐊᑐᕐᓂᑰᕗᖅ. ᓴᖅᑲᓕᐊᓯᐅᑉ ᐃᒡᓗᕋᓛᕆᔫᔮᖅᐸᖓ ᓯᓚᑖᓂ, ᐊᒻᒪ ᐃᓗᐊᓂ ᓄᓇᕗᓕᐊᕈᔾᔭᐅᕗᓯ. ᐃᒡᓗ ᐃᖅᑲᐃᑎᑦᑎᓐᓇᖅᐳᖅ ᐊᒥᓱᓂ ᐃᒡᓗᕋᓛᖑᔪᓂ ᑕᑯᕙᒃᑕᓐᓂ ᓄᓇᕗᓕᒫᒥ, ᐊᒻᒪ ᑐᖑᔪᖅᑐᖅ ᑲᓚᖓ ᐊᔾᔨᐸᓗᒋᕙᖓ ᐊᖓᔪᖅᑳᒪ ᓇᖕᒥᓂᖅ ᐃᒡᓗᕋᓛᖓᓐᓂ ᐅᐊᖕᓇᒥ ᑕᓯᐅᔭᕐᔪᐊᒥ, ᐅᕝᕙᓘᓐᓃᑦ ᑲᖏᖅᓱᐊᓗᖕᒥ.

ᐃᒡᓗᕋᓛᖅ ᐃᓯᕈᕕᐅᒃ, ᑕᑕᑕᐅᕗᑎᑦ ᓂᐱᓂᑦ ᐊᒻᒪ ᑕᑯᓐᓇᒐᒃᓴᐅᔪᓂ ᓄᓇᕗᒻᒥ, ᐊᒻᒪ ᐃᕐᙲᓇᑲᐅᑎᒋᑲᓴᒃ ᐊᖏᕐᕋᖅᓯᒪᔫᔮᖅᐳᖓ. ᑎᓴᒪᓂ ᐊᕙᓗᓂ ᓈᓚᒍᓐᓇᖅᐳᑎᑦ ᐅᓂᒃᑳᖅᑐᐊᓂ ᐅᖃᐅᓯᐅᔪᓂ ᐃᓄᑐᖃᕐᓂ. ᐅᑯᐊ ᓂᐱᐅᕗᑦ ᓱᕈᓯᐅᓚᐅᕐᓂᓐᓂ. ᐊᑕᐅᓯᕐᒥ ᑕᕐᕆᔭᓕᐊᖑᔪᒥ ᐃᓕᓴᖅᓯᑲᐅᑎᒋᓚᐅᖅᐳᖓ ᓰᕐᓇᕐᒥ, ᖁᖑᓕᖅ, ᓱᕈᓰᑦ ᑐᓂᓯᓪᓗᑎᒃ ᐃᓄᑐᖃᕐᓄᑦ, ᐊᒻᒪ ᖃᓂᕋ ᓰᓚᐅᖅᐳᖅ ᐃᖅᑲᐅᒪᓂᕐᒥ ᓂᕆᓂᕐᒥ ᐱᕈᖅᓯᐊᖑᔪᒥ. ᖁᙱᐊᖅᖢᓂ ᓱᕈᓯᓂ ᐱᙳᐊᖅᑐᓂ ᐃᓄᒃᑎᑐᑦ ᐊᓇᐅᓕᒑᕐᓂᐅᔪᒥ ᑕᑯᒃᓴᐅᓂᐅᔪᓐᓇᖅᐳᖅ ᐱᔭᐅᔪᒥ ᓯᕈᓯᐅᓚᐅᖅᓯᒪᓂᓐᓂ ᐃᖅᑲᐅᒪᓂᕐᒥ ᐃᒡᓗᓕᒑᕐᔪᖕᒥ. ᑕᒪᒃᑭᓗᒃᑖᖅ ᐃᓕᔭᐅᓯᒪᓂᖓᓂ ᓴᙱᔪᐊᓗᖕᒥ ᐃᒃᐱᒍᓱᖕᓂᐅᕗᖅ ᐊᒻᒪ ᐱᐅᓗᐊᖅᑐᒻᒪᕆᐊᓘᓪᓗᓂ ᓄᓇᕐᔪᐊᒧᑦ ᐊᑐᕐᓂᐅᔪᒥ ᐃᒃᐱᒍᓱᖕᓇᖅᑐᒥ ᐊᖏᕐᕋᖅᓯᒪᓂᓐᓂ, ᑭᓯᐊᓂ ᐊᖏᖃᑎᒌᖕᓂᖅ 1-ᒥᑉᐳᖓ ᓄᓇᕗᒻᒥ.

ᑕᑯᒃᓴᐅᓂᐅᔪᑦ ᖃᐅᑕᒫᒥ ᐅᕙᓐᓂ ᐃᖅᑲᐃᑎᑦᑎᕗᖅ ᐱᒻᒪᕆᐅᓂᖓᓂ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᓄᓈᓂ ᐃᓄᖕᓄᑦ ᑕᐅᕙᓂᕐᒥᐅᑕᐅᔪᓄᑦ. ᓄᓇᖏᑦ ᐃᒡᓗᓕᐅᑉ ᕿᑭᖅᑕᖏᓐᓂ, ᑕᕐᕆᔭᓕᐊᖑᔪᑦ ᐃᓄᖕᓂ ᐊᖅᑯᒻᒥ ᐊᒻᒪ ᒥᑦᑕᕐᕕᖕᒥ, ᑕᑯᒃᓴᐅᓂᐅᔪᖅ ᐊᕐᓇᓂ ᕿᓯᓕᕆᔪᓂ ᓯᒡᔭᒥ, ᐊᒻᒪ ᓱᕈᓰᑦ ᓯᓚᒥ ᐊᓃᕋᔭᒃᑐᓂ ᐱᒻᒪᕆᐅᔪᐃᓐᓇᐅᕗᑦ ᐊᒻᒪ ᑐᙵᓇᖅᖢᓂ ᐃᓚᒋᔭᐅᕗᑦ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐃᓕᖅᑯᓯᖏᓐᓂ. ᓴᓂᓕᐊᓂ ᐃᓄᓕᒫᓄᑦ ᑐᓵᑎᑕᐅᓂᐅᔪᓂ ᐅᔭᕋᖕᓂᐊᕐᓂᕐᒧᑦ ᒥᑦᑎᒪᑕᓕᐅᑉ ᖃᓂᒋᔭᖓᓂ ᐃᖅᑲᐃᔾᔪᑎᕐᔪᐊᖑᕗᖅ ᑭᓱᑦ ᐅᓗᕆᐊᓇᖅᑐᒦᓐᓂᖏᓐᓂ ᓇᒃᓴᕈᕕᑦ ᐱᕙᓪᓕᐊᑎᑕᐅᓂᐅᔪᒥ ᐊᒻᒪ ᓴᓇᔭᐅᓯᒪᔪᓄᑦ ᓄᓇᑦᑎᓐᓄᑦ. ᑕᒪᒃᑭᓗᒃᑖᖅ ᐃᓕᔭᐅᓂᖓᓂ ᓴᙱᔪᐊᓘᓪᓗᓂ ᐊᑐᕐᓂᑰᕗᖅ ᐆᒻᒪᑎᖓᓐᓃᑦᑐᓂ ᐊᒥᓱᓄᑦ ᐃᓄᖕᓄᑦ, ᐃᖏᕐᕋᐃᓐᓇᕐᓂᐅᔪᒥ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐱᖅᑯᓯᖏᓐᓂ ᐃᓅᓯᖏᓐᓂ.

English

I am Krista Ulujuk Zawadski from Igluligaarjuk and Rankin Inlet, Nunavut. I am one of the co-curators of INUA.

The cabin with videos by Isuma is an amazing and surreal experience. It looks like Zach’s cabin from the outside, and inside you are taken to Nunavut. The building is reminiscent of many cabins I see across Nunavut, and the blue colour is especially similar of my parents own cabin in northern Tasiujarjuaq, or Hudson Bay.

Once inside the cabin, you are encased by sounds and visuals of Nunavut, and almost immediately I feel like I am back home. On the four walls you can listen to the stories told by Elders. These are sounds of my childhood. In one scene I recognized instantly the siirnaq, the mountain sorrel plant, the children shared with the Elders, and my mouth salivated at the memory of eating the plant. Watching kids play Inuit baseball could be a scene taken from my own childhood memories in Igluligaarjuk. The entire installation is a palpable and ethereal experience that makes me feel like I am at home, but yet I am on Treaty One Territory.

The scenes of the everyday remind me of the importance of Inuit Nunaat for the people that live there. The landscapes of Iglulik island, the footage of people on the street and at the airport, the scene of the women cleaning sealskins on the beach, and the children playing outside are all important and intimate aspects of Inuit lives. Juxtapose that with the public hearings about mining near Mittimatalik is a stark reminder of what’s at stake when you bring in development and industry to our land. The entire installation is a powerful experience of what is at the heart of many Inuit, which is the continuation of our ways of life.

Carved Tusk on Base

Victor SammurtokCarved Tusk on Base, 1966

ivory, whale bone, wood, black insets

Collection of the Winnipeg Art Gallery, Twomey Collection, with appreciation to the Province of Manitoba and Government of Canada, 1171.71

Inuktut

ᐅᕙᖓ ᑯᕆᔅᑕ ᐅᓗᔪᒃ ᔭᕙᔅᑭ ᐃᒡᓗᓕᒑᕐᔪᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑲᖏᖅᖠᓂᖅ, ᓄᓇᕗᒻᒥᐅᑕᖅ. ᒥᐊᓂᕆᔨᐅᖃᑕᐅᔪᑦ−ᐃᑲᔪᖅᑎ ᐃᓄᐊᒧᑦ.

ᑖᒻᓇ ᓴᓇᙳᐊᒐᖅ ᓴᓇᔭᐅᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᐃᑦᑐᒻᓄᑦ, ᐅᕝᕙᓘᕝᕙ ᐊᑖᑦᓯᐊᒻᓄᑦ. ᐊᓈᓇᒐ ᐊᑖᑕᑦᓯᐊᖓ, ᕕᒃᑐ ᓴᒻᒧᖅᑐᖅ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐊᒥᓱᑦ ᐃᓚᒃᑲ ᒪᓕᒃᑐᑦ ᑭᓇᐅᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦ ᕕᒃᑐᒧᑦ ᐊᓐᒪᓗ ᐊᑖᑦᓯᐊᒻᓄᑦ, ᐊᒪᐅᕋ ᐃᒐᓛᖅ. ᕕᒃᑐ ᓇᑦᓯᓕᖕᒥᐅᑕᖅ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᒐᓛᖅ ᐊᐃᕕᓕᖕᒥᑦ. ᕿᑐᕐᖓᖏᓪᓗ, ᐃᒡᓗᓕᒑᕐᔪᒻᒥᐅᑕᐅᓕᓚᐅᖅᑐᑦ, ᐱᕈᕐᕕᒻᓂ.

ᑕᑯᓵᕋᑉᑯ ᓴᓇᙳᐊᒐᖅ ᑎᑎᕋᕐᕕᒋᓚᐅᒐᕋ ᐃᓚᓐᓈᕋ. ᐅᓂᒃᑳᖅᐸᑉᓂᐊᑉᓗᓂ ᐃᖅᑲᐅᒪᔭᒃᑲ ᐊᑖᑕᑦᓯᐊᒪ ᐅᓂᒃᑳᖏᓐᓂᒃ. ᐃᖅᑲᐅᒪᔪᖅ ᓴᓇᙳᐊᖅᑎᓪᓗᒍ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑑᒑᑉ ᓯᐅᕋᖏᑦ ᑎᒥᐊᓄᑦ ᐊᓚᖅᓯᒪᔪᖅ. ᑑᒑᖅ ᐱᐅᓂᒋᖅᐹᒋᓚᐅᖅᑕᖏᑦ ᓴᓇᙳᐊᕐᓂᐊᕐᓗᓂ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑎᑎᕋᐃᓐᓇᖅᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᓇᓗᓇᕐᓂᖓᓄᑦ ᓴᓇᓯᒪᓂᖓᓄᑦ. ᐊᑕᐅᓯᖅ ᓴᓇᙳᐊᒐᖅ, ᕕᒃᑐ ᓴᓇᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᐊᐃᕕᐅᑉ ᑐᒑᖓᓂ ᐊᔾᔨᒌᙱᑦᑐᓂᒃ ᑕᑯᒃᓴᐅᔪᓄᑦ. ᐃᓚᖃᖅᑐᑦ ᐊᖑᑦ ᖃᔭᕐᒥ ᒪᖃᐃᑦᑐᖅ ᐊᐃᕕᕐᒥᒃ, ᑎᒻᒥᐊ, ᓇᑦᓯᖅ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐊᕆᒐᓂᐊᑦ. ᓴᓇᙳᐊᖅᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᐊᑎᖃ ᖃᓄᐃᔮᖅᐸᐃᑎᑐᑦ ᐊᐃᕕᐅᑉ ᑑᒑᖓ ᑐᙵᕝᕕᒃ. ᓇᓗᓇᐃᔭᑦᓯᐊᕈᒪᓚᐅᖅᑐᖅ ᓴᓇᙳᐊᖅᓯᒪᔭᖓᓄᑦ.

ᐊᒥᓱᑦ, ᐃᑦᑐᕋ ᓴᓇᙳᐊᖅᓯᒪᑦᓯᐊᕐᓂᖓ ᐃᓱᒪᓇᕈᑎᒋᔭᕋ. ᓴᓇᙳᐊᕐᓂᕆᔭᖓᒍᑦ ᐊᔪᙱᓐᓂᖓ ᑲᒪᑦᓯᐊᕐᓂᖓ ᓴᓇᙳᐊᕐᓂᖓᓄᑦ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᖅᑲᐅᒪᔭᐅᔪᖅ ᐃᓕᖅᑯᓯᖓᓄᑦ. ᐱᕈᖅᓯᐊᖅᓯᒪᔭᖏᑦ ᐃᓚᖏᑦ ᑕᐃᒪᑦᓯᐊᑎᑐᑦ ᓴᓇᙳᐊᕐᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᖃᓄᐃᓐᓂᕆᔭᖓᓄᑦ ᐆᒪᔪᖅ ᐊᒥᓱᓄᑦ ᑭᖑᕚᖏᓐᓄᑦ ᐅᑉᓗᒥ, ᐊᒥᓱᑦ ᐊᒃᓱᕈᖅᑐᑦ ᐱᓕᕆᓂᕐᒧᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓴᓇᙳᐊᕈᓐᓇᕐᓂᕐᒧᑦ. ᑐᙵᕝᕕᒃ ᐃᑉᐱᒋᔭᒧᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑐᕌᖓᔾᔪᑎᒋᔭᖅ ᓴᓇᓯᒪᑦᓯᐊᕐᓂᐊᖓᓄᑦ ᑐᙵᕝᕕᒃᓴᖃᖅᖢᓂ ᐱᔪᒪᓂᒻᓄᑦ ᐅᐱᒋᓂᒃᑯᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐊᓂᕐᓂᒻᓄᑦ.

English

I am Krista Ulujuk Zawadski from Igluligaarjuk and Rankin Inlet, Nunavut. I am one of the co-curators of INUA.

This carving was made by my ittuq, or great grandfather. He was my mother’s father’s father, Victor Sammurtok, and many of my relatives trace their own ancestry to him and my great grandmother, my amauq Igalaaq. Victor was from Natsilik, and Igalaaq was from Aivilik. With their children, they eventually settled in Igluligaarjuk, where I was raised.

When I first saw this piece in the collection I messaged my mom about it. She began sharing with me her memories of her grandfather. She remembers him carving at home, and was often covered in ivory dust. Ivory was a favourite medium of his to carve, and she always makes note of his intricate work. As one whole carving, Victor has carved into the walrus tusk a series of images. These include a man in a qajaq hunting walrus, a qamutik, a bird, a seal and foxes. He has also carved his name in syllabics into the whalebone base. He wanted to make sure we knew he made this carving.

In many ways, my ittuq’s detailed work inspires me. His craftsmanship demonstrates the care he took in his work, and he is remembered as a man of integrity. He raised his family with the same care he took in his work, and that attitude has lived on through many of his descendants today, many of whom are hard working and creative. The standard of care and attention to detail that he set is something I strive to honour and embody.

Continuous Series (Andrew Miller, Moriah Sallaffie, Bethany Horton, Bonnie Maroni, Tuiġana)

Jenny Irene MillerContinuous Series (Andrew Miller, Moriah Sallaffie, Bethany Horton, Bonnie Maroni, Tuiġana), 2015-2016

digital photographs on Epson photo paper

Collection of the artist

Inuktut translation coming soon

Uvanga Kablusiak, apungma atinga Arlin Carpenter, Ikahukmun, amamamunga atinga Holly Nasogaluak Carpenter, tuktuyaktumun.

It’s incredibly special how Jenny Irene Miller spotlights queer identities and offers a platform for our queer relations to share their stories. I don’t necessarily like to use this term often, but I feel like this work fits within my perspective of art that is decolonial. In my view, restrictive binaries forced upon gender and sexuality are one of the most destructive components of colonialism that we are still dealing with today. Jenny’s ongoing practice of care in upholding and sharing these stories beautifully demonstrates how artists can use their voice and perspective to deconstruct colonial systems in a nuanced and tender way.

There is a remarkable amount of power behind being able to bring our whole selves into view, and being able to share the parts of us that have been denied humanity. I don’t have the words to describe how beautiful it is to be able to see autonomous Inuk queerness displayed within the walls of a gallery.

Doll (Hunter dressed in bird feather parka)

Elisapee InukpukDoll (Hunter dressed in bird feather parka), 1989

Eider duck skin, caribou skin, sealskin, rabbit fur, wood, grass, stone

Winnipeg Art Gallery, Gift of JoAnn and Barnett Richling, 2013-107

Inuktut

ᐁ, ᐊᓰᓐᓇᔮᖑᕗᖓ, ᐃᓚᒋᔭᐅᕗᖓ ᑲᒪᔨᐅᓂᕐᒥᒃ ᐱᓇᓱᖃᑎᒌᑦᑐᓄᑦ. ᐃᓄᑦᔪᐊᒥᐅᔭᐅᕗᖓ ᓄᓇᕕᒻᒥ ᑎᐆᑎᐊ:ᑮᒥ ᒪᓐᑐᔨᐊᖑᓂᕋᕐᑕᐅᕙᒻᒥᔪᒥ ᑯᐯᒃᒥ ᓄᓇᓯᒪᓂᕐᓴᐅᓱᖓᔪᖓ.

ᐃᓕᓴᐱ ᐃᓅᓯᕐᒥᓂ ᐊᒥᓱᒻᒪᕆᐊᓗᓐᓂᒃ ᐃᓅᔭᓕᐅᖃᑦᑕᓯᒪᓕᕐᑐᖅ. ᐅᓇ ᑌᒫᑐᐃᓐᓇᑎᖕᖏᑕᕋ ᑮᑕ ᐊᑖᑕᑦᓯᐊᕋᓄᑦ ᐃᕐᙯᑎᒋᑦᓱᒍᓘᕋᒃᑯ! ᐊᑖᑕᑦᓯᐊᕋ ᓯᒥᐅᓂ ᐊᒪᕈᕐᑐᖅ ᐅᐃᑖᓗᒃᑐᖅ ᐊᓪᓚᓯᒪᔪᓕᐅᖃᑦᑕᓯᒪᕗᖅ ᐊᓪᓚᓯᒪᔪᑦᓴᓂᒃ ᐊᒥᕐᖃᖃᑎᒌᒍᑎᑦᓴᒥᓂᒃ ᖃᐅᔨᒪᔭᒥᓂᒃ ᐅᓪᓗᑕᒫᑦ ᐃᓅᓯᕐᒥᓂ ᐊᑑᑎᔭᒥᒍᑦ ᓄᓇᓕᓐᓄᑦ ᓄᑦᑎᓂᖃᓚᐅᕋᑎᒃ ᐊᓪᓚᖃᑦᑕᓯᒪᔭᖏᑦ. ᐊᓪᓚᑕᖏᑕ ᐃᓚᖏᑦ ᐅᓂᒃᑲᐅᓯᖃᕐᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᖃᐅᔨᒪᔭᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᐊᓐᓄᕌᓄᓕᖓᔪᓂᒃ. ᐊᔪᒉᑦᑐᐊᓘᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᐊᓪᓚᑕᕕᓂᖏᑦ ᐃᓕᖓᔪᑦ ᑎᒻᒥᐊᕕᓂᕐᓂᒃ ᐊᓐᓄᕌᓕᐅᕈᓰᑦ! ᑐᑭᓯᒪᔭᒃᑲᑎᒍᓪᓕ, ᐃᓚᒌᖑᑦᓱᑕ ᐊᐅᓪᓛᓯᒪᓂᖅ ᐱᐅᓯᕆᔭᐅᓯᒪᖕᖏᑐᖅ, ᑭᓯᐊᓂ ᐊᑑᑎᒍᓐᓇᖃᑦᑕᓯᒪᒻᒥᔭᕗᑦ ᐃᓚᖓᓂᒃ ᑌᒣᒍᒪᓕᑐᐊᕋᑦᑕ! ᐊᑖᑕᑦᓯᐊᒪ ᐊᓪᓚᓯᒪᔪᖁᑎᖏᑦ, ᐊᔮᓗᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓅᔭᖕᖑᐊᓕᐊᕕᓂᖏᑦ ᐃᓱᒪᖕᖑᐊᕈᑎᒋᓲᕆᕙᒃᑲ ᓇᓃᓪᓗᖓ ᓱᓇᑐᐃᓐᓇᓂᒃ ᓴᓇᓯᒪᔪᓕᐅᖃᑦᑕᕈᓐᓇᓂᕋᓂᒃ ᐊᑐᕐᑐᓴᓂᒃ, ᐃᕐᖃᐅᒪᒍᑎᒋᒐᒃᑭᑦ ᖃᓄᐃᓘᕈᓐᓇᓂᖃᕐᒪᖔᕐᒪ.

Engli

Hello, this is Asinnajaq, a member of the Curatorial team. I am from Inukjuak, Nunavik and have spent most of my time in Tiohtià:ke also known as Montreal, Quebec.

Elisapee has made so many incredibly beautiful dolls in her lifetime. This one is special because it reminds me also of my grandfather! My grandfather Simionie Amarurtaq Weetaluktuk made a journal to document and share his knowledge on daily life and ways of being before moving into town. One portion of the journal documented his knowledge of clothing. It was so remarkable to see the clothes made from birds! To my understanding, in our family and camp it wasn’t the habit, but it could always be done when needed! My grandfather’s journal, and my great-aunt’s doll make me dive into my imagination where I can invent so many creative uses for things, because they remind me what I am capable of.

Doll installation

Multiple ArtistsInuktut

ᑕᖅᑑᔪᖓ, ᑲᖏᖅᖠᓂᕐᒥᐅᑕᐅᔪᖓ. ᐅᕙᖓ ᑮᓚ ᐴᔅ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑲᖏᖅᖠᓂᕐᒥᐅᑕᐅᔪᖓ ᓄᓇᕗᑦ.

ᐃᓱᒪᔭᕌᖓᒪ ᓄᑕᕋᙳᐊᓂᒃ ᑕᐃᒫᒃ ᑐᕌᖓᔪᑦ ᓄᑕᖅᑲᓄᑦ. ᓴᓇᔭᐅᔪᑦ ᓄᑕᕋᙳᐊᑦ ᐃᓄᖕᓂᑦ ᓴᓇᔭᐅᓯᒪᓇᔭᖅᑐᑦ ᓄᑕᖅᑲᓄᑦ ᕿᑎᒍᑎᒋᓂᐊᕐᓗᒋᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐆᑦᑐᕋᖅᑕᐅᔾᔪᑎᒋᑉᓗᒋᑦ ᓴᓇᓂᐊᕐᓗᓂ ᒥᑭᔫᑎᓂᒃ ᐊᓐᓄᕌᓂᒃ ᐱᒋᐊᖅᑳᖅᑎᓐᓇᒋᑦ ᐊᓐᓄᕌᒋᔭᐅᔪᓂᒃ ᐅᑭᐅᖅᑯᖅᑐᓗᐊᙱᓐᓂᖏᓐᓂ.

ᐅᖃᐅᓯᖃᕈᒪᔪᖓ ᐱᒋᐊᕐᓗᒍ ᓄᑕᕋᙳᐊᑦ ᓂᕐᔪᑎᐅᔪᓂᒃ ᑭᓯᐊᓂ ᐸᕐᓇᒃᑐᑦ ᓄᑕᕋᓛᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᐊᒪᐅᑎᒥ. ᐊᒪᐅᑎ ᐊᑐᖅᑕᖅᓯᒪᔭᕗᑦ ᓄᑕᕋᓛᕗᑦ ᐅᖅᑰᑎᒋᓂᐊᕐᓗᒍ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᖃᓂᒋᐊᖅᑎᓐᓂᐊᓗᒋᑦ ᐅᕙᑉᑎᓐᓄᑦ. ᐃᑲᔪᖅᑐᑦ ᐃᑉᐱᓐᓂᐊᕐᓂᕆᔭᐅᓂᐊᖅᑐᓂᒃ ᓄᑕᕋᓛᒧᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑭᓇᑐᐃᓐᓇᖅ ᐊᒫᖅᑐᒧᑦ. ᐃᑲᔪᖃᑕᐅᔪᖅ ᓄᑕᕋᓛᒧᑦ ᐊᑦᑕᕐᓇᙱᓐᓂᖓᓄᑦ. ᐃᓱᒪᔪᖓ ᑕᑯᓐᓇᐅᓂᖏᑦ ᓂᕐᔪᑏᑦ ᐸᕐᓇᒃᑐᑦ ᓄᑕᕋᓛᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᑕᑯᑎᑦᑎᔪᑦ ᓂᕐᔪᑏᑦ ᓇᒡᓕᒍᓱᖃᑕᐅᒻᒪᑕ ᓄᑕᕋᓛᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᒥᐊᓂᕆᔪᒪᓂᖏᑦ ᐊᑦᑕᕐᓇᙱᑦᑐᒃᑯᑦ. ᑕᐃᒪᐅᓪᓚᕆᒃᑐᖅ ᑭᓇᑐᐃᓐᓇᖅ ᓴᓇᓗᓂ ᓄᑕᕋᙳᐊᕐᒥᒃ ᐊᓈᓇᐅᑉᓗᓂ ᑕᑯᑎᑦᑎᔪᖅ ᐱᒻᒪᕆᐅᔪᓄᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓇᓗᓇᐃᒃᑯᑕᐅᑉᓗᓂ ᐊᓈᓇᐅᔪᓄᑦ ᐃᓅᓯᑉᑎᓐᓂ. ᐊᓈᓇᐅᔪᑦ ᓯᕗᓪᓕᖅᐹᒻᒪᕆᐅᔪᑦ ᐃᓅᓯᑉᑎᓐᓂ ᐃᓅᒐᓗᐊᕈᕕᑦ ᐅᕙᑉᑎᒍᑦ ᐅᕝᕙᓘᓐᓃᑦ ᐊᐃᕕᖅ ᓄᑕᕋᙳᐊᑎᑐᑦ ᓴᓇᔭᐅᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᐃᕙ ᑰᑐᒃᒧᑦ.

ᐱᖃᑖ ᓄᑕᕋᙳᐊᖅ ᐅᖃᐅᓯᕆᓗᒍ ᐊᖑᑦ ᑎᒍᒥᐊᖅᑐᖅ ᕿᔪᖕᒥᒃ. ᑕᑯᒑᖓᑉᑯ ᐃᓱᒪᓱᖅᑐᖓ ᐅᖁᒪᐃᑦᑐᓂᒃ ᐊᖑᑎᑦ ᑎᒍᒥᐊᓲᖑᖏᓐᓄᑦ. ᐃᓕᖅᑯᓯᒃᑯᑦ ᐱᔨᑦᑎᕋᐅᑎᒋᔭᐅᔪᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑲᒪᒋᐊᖃᖅᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᑕᒪᒃᑭᒃᑯᑦ ᐊᑐᖅᑕᐅᔪᓄᑦ ᒪᖃᐃᓐᓂᐊᕐᓗᓂ. ᖃᓄᐃᒃᑲᓗᐊᖅᑎᓪᓗᒍ ᓯᓚ -50°C, ᐃᓚᖏᑦ ᓂᕆᒋᐊᖃᕐᒪᑕ. ᐃᓱᒪᔪᖓ ᑖᒻᓇ ᐊᑐᖅᑕᐅᔪᑦ ᓱᓕ, ᐅᑉᓗᒥᐅᔪᒥ. ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐊᖑᑎᑦ ᐊᒥᓱᑦ ᓱᓕ ᒪᖃᐃᖃᑦᑕᖅᑐᑦ.

ᐱᖃᑖ ᓄᑕᕋᙳᐊᖅ ᐅᖃᐅᓯᕆᔪᒪᔭᕋ ᓄᑕᕋᙳᐊᖅ ᑲᒃᑭᓂᓕᒃ. ᓄᑕᕋᙳᐊᖅ ᑎᒍᒥᐊᖅᑐᖅ ᐱᒻᒪᕆᐅᔪᒥᒃ ᑕᑯᑐᐃᓐᓇᕐᓗᒍ ᑲᒃᑭᓂᓕᖓᓄᑦ. ᑲᒃᑭᓂᓖᑦ ᓱᑕᐃᕈᑕᐅᖅᑲᔭᖅᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᑐᒃᓯᐊᖅᑐᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᓂᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐊᑯᓂᐅᔪᒃᑯᑦ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐱᖁᔭᐅᓯᒪᙱᑦᑐᑦ ᑕᒪᓐᓇ ᐊᑐᕐᓗᒍ. ᑕᐃᒪᐃᑎᓪᓗᒍ ᐊᑐᕈᓐᓇᖅᑕᐅᑎᓪᓗᒍ ᓱᓕ, ᐊᒥᓱᑦ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐊᑐᕈᓐᓃᖅᓯᒪᔭᖏᑦ ᐅᑉᐱᕐᓂᖅ ᑎᕆᒍᓱᖕᓂᕐᒧᑦ. ᑭᓯᒥᑐᐃᓐᓇᖅ ᖁᓕᑦ ᐅᑭᐅᑦ ᑭᖑᓂᐊᓂ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ, ᐱᓗᐊᖅᑐᒍ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐊᕐᓇᐃᑦ ᐊᑐᖅᐸᓪᓕᐊᒃᑲᓐᓂᖅᓯᒪᔭᖏᑦ. ᑲᒃᑭᓂᓕᕆᓂᕐᒧᑦ ᐅᑎᖅᑎᑕᐅᓂᕐᒧᑦ ᐊᐅᓚᕙᓪᓕᐊᔪᓂᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑕᑯᒐᓐᓈᖅᑎᑦᑎᑕᐅᓪᓗᑎᒃ ᑲᓇᑕᐅᑉ ᐅᑭᐅᖅᑕᖅᑐᓕᒫᖓᓂ. ᑲᒃᑭᓂᓕᕗᑦ ᐅᑎᖅᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᐅᕙᑦᑎᓐᓄᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐅᕙᑦᑎᓄᑐᐃᓐᓇᖅ. ᐅᕙᖓ ᓯᕗᓪᓕᖅᐹᖑᔪᖓ ᐃᓚᓐᓂᑦ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᑲᒃᑭᓂᓕᖃᖅᑐᒥᑦ ᓴᓇᔭᒃᑲ ᐊᒐᓐᓄᑦ. ᐃᖅᑲᐅᒪᔪᖓ ᖁᒃᓴᓱᒃᑎᓪᓗᖓ ᖃᓄᖅ ᐊᓯᖏᑦ ᐃᓱᒪᖃᕐᓂᐊᕐᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦ ᑭᓯᐊᓂ ᑖᓐᓇ ᐱᔪᒪᑦᑎᐊᖅᓯᒪᔭᕋ ᐱᓕᕆᐊᕆᓗᒍ. ᐃᓕᓐᓂᐊᖃᑕᐅᔪᖓ ᐃᓕᓴᐃᔨᐅᓂᕐᒧᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓱᒫᓘᑎᖃᓚᐅᖅᑐᖓ ᖃᓄᖅ ᐃᓕᓐᓂᐊᕐᕕᐅᑉ ᐊᐅᓚᑦᑎᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᑦ ᐃᓱᒪᓇᔭᕐᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦ, ᑭᓯᐊᓂ ᐃᑉᐱᒋᓂᖃᐃᓐᓇᖅᑐᖓ ᑭᓯᐊᓂ ᐃᓱᒪᒃᓴᖅᓯᐅᕈᑎᔅᓴᓂᒃ ᖃᓄᐃᓕᐅᕋᔭᖅᑐᓄᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᑲᔪᖅᑕᐅᓂᖅ ᐃᖅᑲᓇᐃᔭᖅᑎᓂᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓕᓐᓂᐊᖅᑎᓂᑦ ᐱᔾᔪᑎᒋᓪᓗᒋᑦ.

ᑭᖑᓪᓕᖅ ᓄᑕᕋᙳᐊᖅ ᐅᖃᐅᓯᕆᔪᒪᔭᕋ ᐆᒪᔫᔮᖅᑐᒥᒃ. ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐅᓂᒃᑳᓕᐊᖏᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐅᓂᒃᑳᑦ ᐱᒻᒪᕆᐅᔪᖅ ᐅᖃᐅᓯᒃᑯᑦ ᖃᖓᓂᑕᐃᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓕᓴᐃᓂᕐᒧᑦ. ᓄᑕᕋᙳᐊᖅ ᐊᑕᐅᓯᑐᐃᓐᓇᒧᑦ ᐃᓱᒪᒃᓴᕆᙱᑕᕋ ᐅᓂᒃᑳᓕᐊᓄᑦ ᑭᓯᐊᓂ ᐃᖅᑲᐃᑎᑦᑎᔪᖅ ᐅᕙᓐᓄᑦ ᖃᓄᖅ ᑲᑉᐱᐊᓇᖅᑐᓂᒃ, ᓄᑕᕋᙳᐊᖅᑎᑐᑦ, ᐃᓚᖏ ᐅᓂᒃᑳᓕᐊᖑᔪᑎᑐᑦ. ᑕᒪᕐᒥᒃ ᐅᓂᒃᑳᓕᐊᑦ ᐃᓕᓐᓂᐊᕈᑕᐅᔪᑦ, ᐃᓕᓴᐃᓂᖅ

ᐅᕝᕙᓘᓐᓃᑦ ᐃᓕᒪᓱᒋᔭᐅᓂᖓᓄᑦ. ᐆᖅᑑᑎᒋᓗᒍ ᐅᓂᒃᑳᓕᐊᖅ ᖃᓪᓗᐸᓪᓗᐃᑦ ᐅᖃᐅᑎᔭᐅᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᓄᑕᕋᐃᑦ ᓱᑯᒧᐊᖅᑕᐃᓕᒪᖁᓪᓗᒋᑦ.

ᑭᖑᓪᓕᖅ ᐅᖃᐅᓯᕆᔪᒪᔭᕋ ᓄᑕᕋᙳᐊᖅ ᓴᓇᔭᐅᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᐊᒥᓱᓂᒃ ᐊᔾᔨᒌᙱᑦᑐᓂᒃ ᐊᑐᖅᑕᐅᔪᓂᒃ ᐊᓗᕈᑎᒃᓴᓂᒃ. ᐊᓗᕈᑎᒃᓴᖃᙱᑦᑐᖅ, ᒥᖅᑯᓂᒃ, ᐅᕝᕙᓘᓐᓃᑦ ᐊᒥᓂᒃ ᓴᓇᔭᐅᓯᒪᔪᓂᒃ. ᓴᓇᔭᐅᓯᒪᓇᔭᖅᑐᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓴᓇᔭᐅᑐᐃᓐᓇᖅᑐᑦ ᓱᓕ ᓱᓇᑐᐃᓐᓇᓂᒃ ᐊᑐᕈᓐᓇᖅᑕᒥᓂᒃ. ᐊᒥᓱᑦ ᐃᓱᒪᒃᓴᖅᓯᐅᕈᑎᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐊᔾᔨᒌᙱᑦᑐᑦ ᓄᑕᕋᙳᐊᓄᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓱᒪᔪᖓ ᑕᑯᑎᑦᑎᔪᖅ ᐃᓕᑕᕐᓇᖅᑐᓂᒃ ᓇᑭᙶᕐᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦ. ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐃᓱᒪᒐᔪᒃᑐᑦ ᑕᒪᑦᑕ ᐊᔾᔨᒌᓐᓂᐅᔪᒍᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑕᒪᑦᑕ ᐊᑕᐅᓯᕐᒥᑦ ᓇᑭᙶᖅᓯᒪᔪᒍᑦ. ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᓄᓇᖓᑦ ᑲᓇᑕᒥ ᑕᓯᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᑎᓴᒪᓄᑦ ᐊᐅᓚᑕᐅᔪᓄᑦ ᓄᓇᓕᓐᓄᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓄᓇᓕᖃᖅᑐᓄᑦ. ᐃᓕᖅᑯᓯᕆᔭᑦᑎᒍᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ, ᐊᔾᔨᒌᙱᑦᑐᓂᒃ ᐊᑐᖃᑦᑕᖅᑐᑦ ᐊᓐᓄᕌᓂᒃ ᑕᑯᔪᓐᓇᖅᑕᑎᒃ ᑕᑯᓗᒍ ᓄᑕᕋᙳᐊᖅ; ᐃᓚᖏᑦ ᐊᔾᔨᒌᙱᓐᓂᖏᑦ ᐊᔾᔨᑲᓯᒌᒃᑐᑦ ᓄᓇᓕᒥᐅᑕᓂ.

ᐊᔪᕐᓇᙱᒃᑲᓗᐊᖅᑎᓪᓗᒍ ᑕᑯᓗᒋᑦ ᓄᑕᕋᙳᐊᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑕᑯᑐᐃᓐᓇᕐᓗᒋᑦ ᓄᑕᕋᙳᐊᑐᐃᓐᓇᐃᑦ ᐅᕝᕙᓘᓐᓃᑦ ᓴᓇᙳᐊᒐᐃᑦ. ᐱᓕᒻᒪᒃᓴᖃᑎᒋᕙᒃᑲ ᐃᓗᓕᒫᑦ ᑕᑯᒋᐊᒃᑲᓐᓂᕐᓗᒍ. ᐃᓱᒪᒋᑦ ᓱᒻᒪᖔᑦ ᓴᓇᔭᐅᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦ? ᓇᑭᙶᖅᐸᑦ? ᑭᓇᐅᑉ ᓴᓇᕆᔭᕆᕙᐅᒃ? ᑭᓇᒧᑦ ᓴᓇᔭᐅᓯᒪᕙ? ᑲᒪᒋᒍᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᖃᐅᔨᓂᐊᖅᑐᑎᑦ ᑐᑭᖓᓄᑦ ᓄᑕᕋᖑᐊᖑᑐᐃᓐᓇᐅᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦ.

English

Taqtujunga, kangiq&iniqmiutautjunga. I am Kayla Bruce and I am from Rankin Inlet Nunavut.

When I think of dolls my mind automatically goes to children. Originally dolls created by Inuit would have been made for children to play with and to practice making miniature pieces of clothing before they moved onto real sizes when they got older.

I want to start by talking about the dolls that are animals but are packing their babies in their Amautik. An amautik is what we use to keep our babies warm and close to us. It helps with forming bonds between the child and whoever is carrying them. It also helps the child feel safe. I think the representation of the animals packing their babies shows that animals just like us care for their babies and want to keep them safe too. The fact that anyone would create a doll that is a mom shows the importance and significance moms are to our lives. Moms are at the very beginning of life whether you are a human like us or a walrus like the doll made by Eva Kootook.

The next doll I want to draw attention to is the man who is carrying wood. When I see it I think of all the weight that men carry. Traditionally they were the providers and would have to face all the elements to go hunting. It didn’t matter if it was -50℃, their family still had to eat. I think that this still fits in, in a modern day context. Inuit men still do a majority of the hunting.

The next doll I want to draw attention to is the doll with tattoos. This doll holds significance just by the fact that it has tattoos. Tattooing was very nearly stripped away by the missionaries and for a long period of time Inuit were not allowed to do this practice. Even when we were allowed to, lots of people still didn’t because there was a religious taboo around it. It’s only in the last 10 years that Inuit, especially Inuit women have begun to practice again. There is a tattoo revitalization movement and have been workshops across northern Canada. Our tattoos have come back to us and for us only. I myself am the first one in my family to have Inuit tattoos done on my fingers. I remember being so nervous about what others would think but it was something I really wanted to do. I also am in school to become a teacher and was worried about what school administration would think, but I have felt nothing but curiosity and support from both staff and students about them.

The last doll I want to draw close attention to is the doll that looks like a creature. Inuit stories and legends are a major part of oral history and teachings. This doll doesn’t make me think of one story but it does remind me of how eerie, like the doll, some of the stories are. All stories have a lesson, a teaching or a deterrent. For example the story of the qallupilluit were told to keep children from going onto the ice alone.

The last thing I would like to point out about the dolls is that they are made of many different materials. There is no one fabric, fur, or skin that they are done in. They would have been made and are still being made with what is available to the maker. There is a lot of creativity and differences amongst the dolls and I think that shows the diverseness of Inuit. People like to think that we are all the same and come from the same place. Inuit Nunangat within Canada stretches along 4 territories and provinces. Within our culture and people, there are different styles of clothing which you can see when looking at the dolls; some styles are more common in certain regions.

Although it is easy to look at the dolls and see them just as dolls or art work. I challenge everyone to take a deeper look. Think about why they were created? Where did they come from? Who made it? Who was it for? Do this and you will find deeper meaning than them just being dolls.

Elisapee's Family

Elisapee IshulutaqElisapee's Family, 2012

sugar lift etching, chine colle on paper, 10/12

Winnipeg Art Gallery, Gift of Marnie and Karen Schreiber, 2014-82.1-3

Inuktut

ᑯᕆᔅᑕᐅᕗᖓ ᐅᓗᔪᒃ ᔭᐅᐊᑦᓯᑭ ᐃᒡᓗᓕᒑᔪᒥᖓᓂᑯ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑲᖏᖅᖠᓂᕐᒥᑦ, ᓄᓇᕗᑦ. ᐃᓚᒋᔭᐅᕗᖓ ᐱᒋᐊᖅᑎᑦᑎᖃᑕᐅᓯᒪᓪᓗᖓ ᑑᔅᓱᒥᖓ ᐃᓄᐊ.

ᐊᑐᓂ ᐊᒥᐊᖅᑎᑕᒐᖏᑦ ᐃᓕᓴᐱ ᐃᓱᓪᓗᑕᐅᑉ ᓱᑲᕈᔪᒃ−ᐊᒥᐊᖅᓯᒍᑎ ᐸᓕᐊᒻᒥ ᑭᒡᒐᖅᑐᐃᑎᑕᐅᒻᒪᑦ ᐃᓚᒋᔭᐅᓪᓗᓂ ᑖᔅᓱᒪ ᐃᓚᖏᓐᓂ ᐃᓚᒋᔭᐅᔪᓂᒃ. ᐃᓚᖓᑦ ᐊᒥᐊᖅᑎᑕᐅᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᑕᐃᔭᐅᒍᑎᖃᒃᐳᖅ “ᐊᕐᓇᖁᒃ”, ᐊᑖᑕᒋᓚᐅᖅᑕᖓᓂᒃ. ᐊᓯᒃᑲᓐᓂᖓᓗ ᐊᒥᐊᖅᑎᑕᐅᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᑕᐃᔭᐅᒍᓯᖃᕆᕗᖅ “ᐊᕗᓂᖅ”, ᐊᓈᓇᒋᓚᐅᖅᑕᖓᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑭᖑᓪᓕᖅᐹᖅ ᐊᒥᐊᖅᑎᑕᐅᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᓱᕈᓯᖑᐊᒍᓪᓗᓂ ᑕᐃᔭᐅᒍᓯᖃᑉᐳᖅ “ᒪᓚᐃᔭ”, ᖃᑕᙳᑎᖓᓂᒃ. ᑲᑎᓪᓗᒋᑦ ᐊᒥᐊᖅᑎᑕᐅᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᓴᕿᑎᔅᓯᒻᒪᑕ ᐱᖓᓲᓕᓯᒪᔪᓂᒃ ᐊᒥᐊᖅᑎᑕᒐᕐᓂᒃ. ᐱᖓᓲᓕᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᑕᐃᒃᑯᐊᖑᖁᔨᔪᑦ ᐊᑐᕐᒪᑕ ᐱᓕᕆᐊᕆᓇᓱᐊᖅᑕᖓᓂ ᐊᕐᓇᒥᒃ ᐊᖑᑎᒥᓪᓗ ᕿᑐᙵᓕᑦ ᐃᓚᒋᑦ ᐃᓄᓐᓂ.

ᓱᑲᕈᔪᒃ−ᐊᒥᐊᖅᓯᒍᑎ ᐊᑐᖅᑕᐅᓲᖑᒻᒪᑦ ᓴᓇᒍᑕᐅᓗᓂ ᐊᒥᐊᖅᑎᖅᓯᒪᔪᓂᒃ ᑎᑎᖅᑐᖅᓯᒪᓗᑎᒃ ᑎᑎᖅᓯᒪᓗᑎᒃ ᐸᓕᐊᕐᒥ ᐊᑐᕐᓗᑎᒃ ᐊᒥᐊᖅᓯᒍᑎᒥᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓴᑲᕈᔪᒻᒥᒃ. ᐱᓕᕆᐊᕆᓯᒪᔭᖏᑦ ᐃᓕᓴᐱᒪ ᓇᓗᓇᐃᖅᓯᒍᑎᒋᒻᒪᒋᑦ ᖃᓄᐃᑦᑐᕈᓘᔭᓐᓂᒃ ᐱᓕᕆᔪᓐᓇᕐᓂᖓᓂᒃ ᓴᓇᐅᒐᖁᑎᓕᐅᖅᑎᐅᓂᖓᓂ.

ᐃᓕᓴᓐᓇᕐᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦ ᐃᓚᖏᑕ ᑕᒪᒃᑯᑎᒎᓇ ᓇᓗᓇᐃᔭᑦᑎᐊᖅᓯᒪᓂᖏᑎᒍ ᐊᓐᓄᕌᖏᑕ ᓴᕿᑎᔅᓯᒻᒪᑕ ᐃᒃᐱᓐᓇᕐᓂᖓᓂᒃ ᐊᔾᔨᒌᐸᓘᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦ ᐃᓕᓴᐳᐅᑉ ᐱᓕᕆᐊᕆᖃᑦᑕᖅᓯᒪᔭᖏᑕ. ᐊᒥᐊᖅᑎᑕᐅᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᐃᓕᓴᐱᒧᑦ ᐃᓚᒋᓕᐅᑎᒻᒪᑕ ᑕᕝᕗᖓ ᐃᓄᐊᕐ ᐱᓕᕆᐊᕆᓇᓱᐊᖅᑕᖓᓄᑦ ᐃᓱᒪᒋᔭᐅᓂᖓᒍᑦ ᓯᕗᒧᐊᖃᑎᒌᓐᓂᒻᒧᑦ, ᑐᑭᓯᔭᐅᑎᒐᓱᐊᓪᓗᒍ ᑐᙵᕕᖓ ᑕᐃᑲᖓᑦ ᐃᓅᓕᖅᑎᑕᐅᕕᒋᔭᑦᑎᓐᓂᒃ: ᐃᓚᒋᔭᑦᑎᓐᓂᒃ.

English

I am Krista Ulujuk Zawadski from Igluligaarjuk and Rankin Inlet, Nunavut. I am one of the co-curators of INUA.

Each print of Elisapee Ishulutaq’s sugar-lift etchings is a representation of one of her family members. One print is titled “Arnaquk”, her father. Another print is titled “Auvuniq”, her mother and the last print of a child is titled “Malaiya”, her sister. Put together the prints create a triptych of the prints. The three-fold imagery plays on the theme of nuclear family among Inuit.

A sugar-lift is a way to create painterly marks on an etching plate by using a paint brush and a sugar solution. The work my Elisapee is a testament to her range of skills as an artist.

The familiarity of her family though the details of their clothing creates a sense of intimacy in Elisapee’s work. The prints by Elisapee tie into INUA’s theme through the idea of going forward together, highlighting the foundation from which we come from: our families.

Iqaluullamiluuq (First Mermaid) that can Maneuver on the Land (side-car)

Mattiusi Iyaituk & Etienne GuayIqaluullamiluuq (First Mermaid) that can Maneuver on the Land (side-car), 2016

caribou antler, metal, aluminum, wood, plastic

Collection of Nunavik Inuit Art, Avataq Cultural Institute, DAV.2016.204

Inuktut

ᐊᑎᖃᕐᖁᖓ ᐃᓴᐱᐋᓪ ᐊᕕᖕᖓᖅ ᑦᓴᑭᐊᑦᒥᒃ ᐃᓄᑐᐃᓐᓇᐅᓱᖓ ᐱᕈᕐᓴᓯᒪᔪᖓ ᒪᓐᑐᔨᐊᑉ ᐊᕙᑖᓂ, ᐱᑐᑦᓯᒪᕗᖓᓗ ᐃᒃᓗᓕᒃ ᓄᓇᕕᒻᒧᑦ ᐊᓈᓇᒻᒪ ᐱᕈᕐᓴᕕᒋᑦᓱᒍ ᐃᓅᓕᕐᕕᒋᓯᒪᔭᖓᓄᑦ.

ᑖᒃᑯᐊ ᓴᓇᖕᖑᐊᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᓴᓇᔭᕕᓂᖏᑦ ᒪᑎᐅᓯ ᐃᔦᑦᑑᑉ ᐃᕗᔨᕕᒻᒥᐅᑉ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐁᑦᓯᐋᓐ ᑯᐁᑉ ᐱᓯᒪᔫᑉ Saint-Jean-Port-Joli-ᒥᑦ ᐱᐅᒋᓂᕐᐹᑲᓄᑦ ᓴᓇᖕᖑᐊᓯᒪᔪᓄᑦ ᐃᓚᒋᔭᐅᕗᖅ. ᐊᑦᓯᕋᐅᑎᖃᕐᓱᓂ ᓯᕗᓪᓕᐹᖅ ᐃᖃᓘᓪᓚᒥᓘᖅ ᓄᓇᒥ ᓂᒪᕐᓂᖃᕈᓐᓇᑐᖅ. ᓴᓇᔭᐅᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᓇᓪᓕᐅᓂᕐᓯᐅᓂᖃᕐᑎᓗᒋᑦ Biennale de Sculpture de Saint-Jean-Port-Joli-ᒥ, ᑕᒃᑲᓂ ᓱᔪᖃᕐᓂᐅᔪᑦ ᐱᐅᓯᕆᔭᐅᖏᓐᓇᓱᖑᖕᖏᑐᒥᒃ ᐱᓂᐊᕐᓂᖃᕐᕕᐅᓚᐅᔪᕗᖅ ᐊᑑᑎᔭᐅᓂᖃᓚᐅᔪᒐᒥ ᐃᓗᕐᖁᓯᖃᑎᒌᑦᓴᔭᐅᖕᖏᑐᑦ ᐱᓇᓱᖃᑎᒌᓐᓂᖓᓐᓄᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑕᐅᕐᓯᖃᑎᒌᓐᓂᐅᓱᓂ ᓴᓇᓂᐅᑉ ᐱᐅᓯᖏᓐᓂᒃ, ᐃᓱᒪᔪᖓᓕ ᑕᑯᒥᓇᕐᑐᒪᕆᐅᒋᐊᖓ ᑖᓐᓇ ᐱᓇᓱᑦᑕᐅᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᑕᒪᑐᒥᖓᓗ ᐃᓱᒪᕗᖓ ᐃᓱᒪᒋᑦᓱᒋᑦ ᓱᓇᑐᐃᓐᓇᓂᒃ ᓴᓇᔭᐅᒪᒍᑎᖃᕐᓂᖓᓗ ᖃᓄᐃᓘᕐᑕᐅᒍᑎᖃᕐᓯᒪᓂᖓᓗ. ᓴᓇᔭᐅᒪᒐᒥ ᐊᕐᖁᑎᒥ ᖃᐅᔨᓴᕆᒍᑎᑦᓴᔭᓂᑦ ᑐᑦᑑᑉ ᓇᑦᔪᖏᓐᓂᓗ. ᑕᑯᔪᒍᑦ ᑐᑦᑑᑉ ᓇᑦᔪᖏᑕ ᐊᖏᓂᖏᒃ ᐊᐅᐸᕐᑑᒋᐊᖏᒃ, ᓲᕐᓗ ᑐᑦᑐ ᓇᑦᔪᒌᒃ ᐊᒥᕃᔭᓕᕐᑑᒃ.

ᑖᓐᓇ ᓄᑦᑎᑲᑕᒍᓐᓇᓱᓂ ᓴᓇᔭᐅᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᐃᓱᒪᖃᕈᑎᐅᑦᓱᓂ ᑕᑯᓐᓇᑎᖓ ᐊᕙᑖᒍᑦ ᐱᓱᑦᑐᖅ ᑫᕙᓪᓚᕙᓪᓕᐊᒍᑦᔭᐅᖔᕐᑐᑎᑐᑦ ᐱᐅᓯᖃᖔᕐᓂᐊᑎᓪᓗᒍ. ᐊᑕᕕᖃᕐᓱᓂ ᐃᖏᕐᕋᐅᑎᐅᑉ ᐅᓯᕕᖓᓂᒃ, ᒪᑎᐅᓯ ᐃᖏᕐᕋᐅᑎᒃᑯᑦ ᑕᑯᑦᓴᐅᑎᑦᓯᓂᖃᓚᐅᔪᕗᖅ ᑕᒃᑲᓂ ᓇᓪᓕᐅᓂᕐᓯᐅᑐᓂ, ᐃᖏᕐᕋᔭᑲᑦᓱᓂ ᑕᑯᔭᕐᑐᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᐊᑯᕐᖓᒍᑦ. ᖁᕕᐊᓱᐊᔪᕕᓂᐅᒍᓇᖁᑎᒋᑦᓯᐊᑕᕋ ᓴᓇᓂᖓᓂᓗ ᑕᑯᑦᓴᐅᑎᑦᓯᓂᖃᕐᓂᖓᓂᓗ. ᐃᑉᐱᓂᐊᕈᑎᒋᒐᒃᑯ ᐊᓕᐊᑦᓴᓇᕐᑐᕕᓂᐅᓂᖓ ᑖᑦᓱᒪ ᓴᓇᒪᔫᑉ. ᐅᕙᓐᓄᓕ ᑕᑯᑦᓴᐅᑎᑦᓯᒪᑦ ᖁᕕᐊᓇᕐᓂᖓᓂᒃ ᓄᑖᓂᑦ ᐱᔭᖃᕋᓱᓐᓂᐅᒍᓐᓇᑑᑉ. ᓲᓱᒋᑦᓯᐊᑕᒃᑲ ᒪᑎᐅᓯ ᐃᔦᑦᑑᑉ ᓴᓇᓲᖏᑦ ᐱᐅᓯᕆᔭᐅᖏᓐᓇᓱᖑᖕᖏᑐᓂᒃ ᐱᐅᓯᖃᕐᓱᓂ ᓴᓇᖕᖑᐊᓯᒪᔪᓕᐅᓱᖑᒻᒪᑦ ᐃᓄᑐᐃᓐᓀᑦ ᐃᒣᑉᐳᑦ ᓚᔭᐅᒍᓯᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᖄᖏᐅᑎᓱᖑᒻᒪᑦ.

ᐱᐅᒋᓂᕐᐹᕋᓕ ᑖᒃᑯᐊ ᓴᓇᖕᖑᐊᓱᑎᒃ ᐱᓇᓱᖃᑎᒌᖑᒍᓐᓇᓂᖓᑦ. ᐊᓈᓇᒐ ᐃᓄᑐᐃᓐᓇᐅᒪᑦ ᐃᒃᓗᓕᖕᒥᐅᔭᐅᑦᓱᓂ ᐊᑖᑕᒐᓗ ᒍᐃᒍᐃᖅ ᑯᐯᒃᒥᐅᔭᐅᑦᓱᓂ, ᑌᒣᒻᒪᑦ ᑐᑭᓯᒪᔫᔮᕐᐳᖓ ᑖᑦᓱᒥᖓ ᓴᓇᖕᖑᐊᓯᒪᔪᒥᒃ, ᐅᐱᒍᓱᒍᓐᓇᓂᖃᕋᑦᑕ ᑕᒪᖏᑕ ᓴᓇᖃᑎᒋᕕᓃᒃ ᖃᓄᐃᓘᕈᓯᒋᒍᓐᓇᑕᖏᓐᓂᒃ, ᐃᓗᕐᖁᓯᖏᒃ ᐊᑦᔨᒌᖑᒐᑎᒃ, ᑭᓇᐅᓂᖏᓪᓗ ᐊᕙᑎᖏᓪᓗ ᓲᕐᓗ ᐃᓚᑦᓲᑎᑦᓱᑎᒃ ᐊᑕᐅᓯᐅᓕᓯᒪᔫᒃ. ᓲᕐᓗ ᐅᕙᑦᑐᑦ.

English

My name is Isabelle Avingaq Choquette and I’m an Inuk who grew up in the Montreal area, I have ties to Igloolik Nunavut from my mothers side of the family.

This work created by Matiusi Iyaituk from Ivujivik and Etienne guay from Saint-Jean-Port-Joli is one of my favourite pieces. The title is First Mermaid ( Iqaluullamiluuq ) that can Maneuver on Land. Created at the Biennale de Sculpture de Saint-Jean-Port-Joli, this event was a special occasion for intercultural collaboration and exchanges of technique, I think this is beautifully displayed in this work when you see all the different materials and techniques. Going from road signs to wood and caribou antlers. We notice the main caribou antlers are red, like when the caribou sheds their velvet.

This mobile work was created with the idea that it is not the spectator who walks around the sculpture, but vice versa. It is mounted on a sidecar attached to a motorcycle, Mattiusi actually performed this piece at the Biennale, driving around the visitors. I can just imagine the fun he had making and performing the work. I can feel the playfulness in this piece. For me it expresses the joy of trying new things. I have so much respect for Mattiusi Iyaituk’s work owing to the fact that he pushes the boundaries of what Inuit is perceived to be.

What I love the most about the artwork is the collaboration part. With my mother being an Inuk from Igloolik and my dad a French Quebecois, I can relate to this piece in that way, as we can perceive and appreciate the influences from both artists, their different cultures, identities and environments intertwined into one. Like me.

IQALUVINIUP QAJUNGA (Fish Soup)

Ningiukulu TeeveeIQALUVINIUP QAJUNGA (Fish Soup), 2011

lithograph on paper

Winnipeg Art Gallery, Acquired with funds from the Estate of Mr. and Mrs. Bernard Naylor, funds administered by The Winnipeg Foundation, , 2017-158

Inuktut

ᐊᐃᖓᐃ, ᐳᕌᓐᓴᓐ ᔮᒃᖑᔪᖓ ᐃᓅᓪᓗᖓ ᑕᐅᑐᑦᑕᒥᒍᑦ ᑎᑎᖅᑐᒐᐅᔭᖅᑎᐅᔪᖓ ᐴᔅᑦᕕᐅᓪ ᓄᓇᑦᓯᐊᕗᑦᒥ.

ᐃᖃᓗᒥᓂᖅ ᐆᔪᕐᒧᑦ ᐆᓇᔪᑦᑐᒥ ᑐᙵᓇᕐᓂᕐᒥᓪᓗ ᐃᑉᐱᒍᓱᓕᕈᑎᒋᓲᕋ. ᐊᓃᕋᔭᓚᐅᖅᓱᖓ ᐊᐳᒻᒥᑦ, ᐊᖏᕐᕋᕋᔭᖅᑐᒍᑦ, ᐃᓯᕐᓗᑕ ᓇᐃᒪᓗᑕ ᐆᓯᒪᔪᓂᑦ ᐅᑲᓖᑦ ᓂᕿᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᑭᐊᕋᑦ, ᐸᑏᑏᑦ, ᑳᐸᑦᔅ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᖃᓗᑦᑕᐅᕋᑖᖅᑐᒥᓂᕐᒥᒃ. ᑲᒫᓗᑉᐳᑦ ᖃᐅᓯᐅᓪᓗᑎᒃ ᐲᕋᔭᖅᑕᕗᑦ ᐊᓯᖏᓐᓂᓪᓗ ᐸᓂᖅᑐᓂᑦ ᐊᓐᓄᕌᕐᓗᑕ, ᖃᑕᙳᑎᒃᑲᓗ ᐃᖏᕋᔭᖅᑐᒍᑦ ᓂᕆᖃᑕᐅᓕᕐᓗᑕ ᐊᓗᕝᕕᖃᕐᓗᑕ ᒪᒪᖅᑐᐊᓗᒻᒥᑦ. ᑕᕆᐅᓕᒃᑲᓐᓂᕋᓛᕐᓗᑎᒃᑯᑦ ᐸᐸᒥᓪᓗ ᓂᕆᓚᐅᙱᓐᓂᑦᑎᓐᓂᒃ, ᖁᔭᓕᔪᐃᓐᓇᐅᕗᒍᑦ ᓂᕆᓂᐊᖅᑕᑦᑎᓐᓂᒃ. ᐅᖃᐅᓯᖃᕈᓐᓇᑦᑎᐊᖅᑐᖓ ᐊᔾᔨᒌᙱᑦᑐᑦ ᓂᖀᑦ ᐃᓕᔾᔨᕕᓐᓃᑦᑐᑦ ᐊᒥᒐᓗᐊᓪᓚᕆᑦᑐᑦ. ᓯᕗᓪᓕᖅᐹᒥ ᔅᑐᕌᐱᐊᕆᒥᒃ ᓂᕆᒋᐅᕋᒪ, 13-ᓂᒃ ᐅᑭᐅᖃᔪᔪᖓ! ᑕᒪᓐᓇᐅᓪᓗᓂ ᐊᑭᑐᔪᕐᔪᐊᕐᓂᖏᓪᓗ, ᓂᐅᕕᓗᐊᕈᓐᓇᓚᐅᙱᑦᑐᒍᑦ ᐸᑏᑎᑯᑖᓂᒃ ᐅᖅᓱᒨᖅᓯᒪᔪᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓇᓗᐊᙳᐊᓂᒃ. ᖁᔭᓕᓇᖅᑯᖅ, ᐊᖑᓇᓱᒍᓐᓇᕋᑦᑕ, ᐃᖃᓪᓕᐊᕈᓐᓇᖅᓱᑕᓗ ᐊᑐᑦᑎᐊᕈᓐᓇᕋᑦᑕᓗ ᓄᓇᒥ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓂᕐᔪᑎᓂᑦ ᐆᒪᔾᔪᑎᒋᓪᓗᑎᒍ. ᐊᒥᓱᐊᖅᑎ, ᓴᐅᓂᕐᒧᑦ ᑮᓯᒐᔭᖅᑐᖓ, ᐊᑖᑕᒐ ᐃᓪᓚᖅᓯᓪᓗᓂ ᐅᖃᕋᔭᖅᑐᖅ, “ᑖᓐᓇ ᐃᓕᓐᓄᑐᐊᖅ ᐱᐅᔪᖅ!”. ᐃᓅᓯᖅ ᐅᑭᐅᖅᑕᖅᑐᒥ ᐊᑦᓱᕈᓐᓇᖅᑐᖅ, ᑭᓯᐊᓂ ᐃᖃᓗᒥᓂᖅ ᐆᔪᖅ ᐊᑐᐃᓐᓇᐅᖏᓐᓇᐅᔭᓚᖅᑐᖅ ᐊᕿᐊᕈᑦᑎᓐᓂᒃ ᐆᓇᖅᓯᓪᓗᓂ ᓄᑭᑖᑦᓯᐊᖅᓱᑕᓗ ᒪᔪᕋᕐᓂᕐᒧᑦ ᓯᑐᕋᕐᓂᕐᒧᓪᓗ ᖃᖅᑲᓂᑦ, ᓇᐹᖅᑐᓕᖕᓂᒃ ᖃᐅᔨᒐᓱᐊᖅᑎᓪᓗᑕ ᖃᓂᒋᔭᑦᑎᓐᓂᓪᓗ ᖁᕕᐊᒋᔭᖃᖅᓱᑕ. ᒥᓯᖃᑦᑕᖅᓱᒋᑦ ᐊᓈᓇᑦᓯᐊᑉ ᐸᓚᐅᒐᔾᔨᐊᖏᑦ ᖃᔪᕐᒧᑦ, ᖁᔭᓕᕗᒍᑦ ᑕᕆᐅᑉ ᑭᓱᖃᐅᕐᓂᖓᓄᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓚᒌᖑᓪᓗᑕ ᓂᕆᒍᓐᓇᕋᑦᑎᒍ. ᑏᕕᑉ ᑎᑎᖅᑐᒐᐅᔭᖓᑦ ᑕᑯᓪᓗᒍ ᓴᖑᐃᓪᓛᔪᑦ ᐆᔭᐅᔭᑦ, ᐃᖃᓘᑉ ᐸᐱᕈᖏᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐅᑲᓕᐅᑉ ᓂᕿᖏᑦ ᑭᐅᕋᑦ, ᖁᖓᑐᐃᓐᓇᓕᖅᑯᖓᓕ ᐃᖅᑲᐅᒪᓪᓗᒋᓗ ᓂᕆᒐᔪᓚᐅᖅᑕᑦᑎᓐᓂᒃ ᒪᒪᕆᓪᓚᕆᖃᑦᑕᔪᔭᕋᓂ.

English

Hello, my name is Bronson Jacque and I am an Inuit visual artist from Postville, Nunatsiavut.

Fish soup evokes such a warm and welcome feeling for me. After a day playing in the snow, we would return home, walking through the door to the aroma of boiled carrots, potatoes, cabbage and freshly caught fish. Flicking off our wet boots and changing into dry clothes, my siblings and I would excitedly pull a chair up to the table to a steaming bowl of goodness. Sprinkling on a bit of extra salt and pepper before digging in, we are all thankful for our meal. It would be generous to say that the variety of food stocking the shelves is limited. The first time I had a strawberry, I was 13! That compounded with the exorbitant prices, it was hard to afford much besides French fries and ramen. Thankfully, we are able to hunt, fish and respectfully use the land and wildlife to survive. Often, I’d bite into a stray bone, to which my father would laugh and say, “That’s only good for you!”. Life in the north can be hard, but fish soup was always around to warm our bellies and fuel our days climbing and sliding down hills, exploring the woods and enjoying our humble surroundings. Dipping Nan’s home-made bread into the broth, we give thanks to the sea’s bounty and our family to share it with. When seeing Teevee’s print with it’s swirls of greens, fish tails and carrots, I cannot help but smile and reminisce on the humble dish that I’ve always been eager to enjoy.

Fishing at the Weir

Olajuk KigutikakjukFishing at the Weir, 1980

stone, whalebone

Government of Nunavut Fine Art Collection, On long-term loan to the Winnipeg Art Gallery, 1.81.2 a-x

Inuktut

ᐊᑎᕋ ᔪᐃ ᐅᕼᑲᓐᓄᐊᒃ. ᓄᓇᖃᖅᑐᖓ ᐃᖃᓗᒃᑑᑦᑎᐊᖅ, ᓄᓇᕗᑦᒥ.

ᑎᖕᒥᐊᑦ ᒥᑉᐸᓪᓕᐊᔪᑦ ᓴᐅᓂᕕᓃᑦ ᖁᓕᑦᑎᐊᖏᑦᑎᒍᑦ.

ᑎᓴᒪᑦ ᐊᖑᓇᓱᒃᑎᑦ ᐃᖏᕐᕋᓂᕐᒦᑦᑐᑦ ᑲᑭᕙᒃᓯᒋᐊᕐᐳᑦ – ᐃᖃᓗᖕᓂ ᐃᒫᓃᑦᑐᓂᒃ.

ᑖᒃᑯᐊᓗ ᐃᖏᕐᕋᓂᒃᑰᖅᐸᓪᓕᐊᓪᓗᑎᒃ ᕿᑐᕐᖏᐅᕐᕕᒋᓂᐊᖅᑕᖏᓐᓗᑦ, ᑭᓯᐊᓂᓕ ᑖᒃᑯᐊ ᐃᖃᓗᐃᑦ ᓇᒧᙵᐅᔪᓐᓇᐃᓪᓗᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᐅᔭᖅᑲᓄᑦ ᖃᓕᕇᓕᕐᓯᒪᔪᓂᒃ ᐊᖑᓇᓱᒃᑎᓄᑦ ᐋᖅᑭᒃᑕᐅᓚᐅᕐᑐᓂᒃ ᓯᕗᓂᐊᖑᑦ ᐃᑲᕐᕈᑎᒥ.

ᐅᑯᐊ ᐅᔭᕋᒐᓚᐃᑦ ᐊᒻᒪ ᓴᐅᓂᒐᓚᐃᑦ ᑲᑎᓯᒪᑦᑎᐊᕐᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑎᑎᕋᐅᔭᖅᑎᐅᑉ ᓴᖅᑭᔮᖅᑎᑦᑎᐊᕐᓯᒪᓪᓗᓂᐅᒃ ᑎᑎᕋᐅᔭᕐᑕᖓ. ᓄᓇᑎᑑᙱᖢᑎᒃ, ᐊᖑᓇᓱᒃᑎᐅᔪᑦ ᐊᒻᒪ ᓂᕐᔪᑎᐅᔪᑦ ᖃᐃᕋᑦᑐᐃᑦ. ᐅᓇ ᐊᔾᔨᒋᙱᓐᓂᐅᔪᖅ ᓴᖅᑭᔮᖅᑐᒥᒃ ᓱᖅᑯᐃᓇᕐᓯᓕᖅᑎᑦᑎᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᑕᒪᐃᓐᓂ ᓂᕐᔪᑎᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪ ᐃᓚᒋᔭᐅᔪᓂᒃ; ᑕᐅᑐᙳᐊᕋᒃᑯ ᐃᒪᖅ ᑰᒐᓛᒃᖢᓂ, ᐃᖃᓗᐃᑦ ᓴᖅᑭᑲᑕᒃᖢᑎᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓂᐱᖃᔮᙱᖢᓂ ᑖᒃᑯᐊ ᐊᖑᓇᓱᒃᑏᑦ ᐅᑕᖅᑭᓂᖏᓐᓂᒃ.

ᐃᒃᐱᖕᓇᖅᖢᓂ ᓂᕆᐅᒃᑐᑦ ᓇᓕᐊᒃ ᐃᖃᓗᖄᕐᓂᐊᕆᒃᓴᖏᓐᓂᒃ. ᐱᒃᑯᒋᔭᖃᕐᓂᖅ ᐊᖑᓇᓱᖕᓂᕐᒥᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓂᕆᐅᓗᐊᕌᓗᖃᑦᑕᕆᐊᖃᙱᓐᓂᖅ.

English

My name is Zoe Ohokannoak. I am from Ikaluktutiak, Nunavut.

Birds descending across the scenery of rapids of bone.

Four hunters in the flowing water bringing down their Kakivaks – a type of spear – to pierce the fish below.

Which have been ascending the rapids to reach their mating grounds, the fish have found themselves enveloped in a trap of carefully stacked rocks that the hunters had set previously.

The combination of stone and bone materials contrast and compliment each other making the artist’s work clear. Unlike the nuna, the hunters and the animals are carved smooth. This differing texture brings to life an entire sensory experience with the details of each creature and item involved; I envision water flowing, fish splashing and eerie silence of the hunters waiting.

Sensing the tension in the air of who’s going to get the first catch of the day. Being proud of a successful hunt and not to hold high expectations.

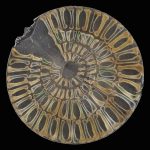

Four Seasons of the Tundra

Ruth QaulluaryukFour Seasons of the Tundra, 1991-1992

embroidery floss on wool stroud

Winnipeg Art Gallery, Gift of the Volunteer Committee to the Winnipeg Art Gallery, G-93-26 a-d

Inuktut

ᐊᐃᖓᐃ, ᐊᓯᓇᔭᐅᔪᖓ, ᐃᑲᔪᖅᑎ ᒥᐊᓂᕆᔨ ᑕᑯᒐᓐᓈᒐᖃᕐᕕᒻᒥ. ᐃᓄᒡᔪᐊᖅ, ᓄᓇᕕᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓅᓯᓗᒃᑖᖅᑲᔭᕋᓂ ᑎᐅᑎᐊ:ᑮᒦᓯᒪᔪᖓ ᖃᐅᔨᒪᔭᐅᔪᖅ ᒪᓐᑐᕆᐊᓪ, ᑯᐱᒃ.

ᐱᐅᔪᒻᒪᕆᐊᓗᒃ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᓄᓈᑦ ᓄᓇᒋᔭᖅ ᐊᐅᓚᓂᒃᑯᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐊᓯᙳᕐᓂᕐᒧᑦ. ᐅᑭᐅᖑᑎᓪᓗᒍ ᑕᑯᓯᒪᔪᒍᑦ ᓄᓇᐃᑦ ᐱᕈᖅᐸᓪᓕᐊᑎᓪᓗᒋᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐊᐅᒃᓯᖅᐸᓪᓕᐊᑎᓪᓗᒋᑦ, ᐊᓯᙳᖅᐸᓪᓕᐊᔪᑦ ᐊᐳᑎ ᖃᑯᕐᓂᖓ ᑐᖑᔪᖅᑕᙵᖅᑐᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐊᐅᐸᔮᖅᑐᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑲᔪᖅᑐᑦ. ᖃᐅᓪᓗᐊᕐᔪᑉ ᓴᓇᙳᐊᒐᖏᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑭᓗᖏᑦ ᓴᓇᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᐊᐅᓚᓂᖓ ᐃᖏᕐᕋᓂᖃᖅᑐᖅ ᐅᕙᒻᓄᑦ ᖁᑉᐸᕙᓪᓕᐊᔪᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑲᑕᒃᐸᓪᓕᐊᔪᑦ ᑭᖓᓂᑦ, ᑲᐃᕕᕙᓪᓕᐊᔪᖅ ᑰᒃ. ᑖᑉᓱᒪ ᓴᓇᙳᐊᒐᖓ ᐃᖅᑲᐅᒪᔾᔪᑎᑦᓯᐊᕙᒃ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᓄᓇᖓᑦ ᑐᑭᓕᐅᖅᑕᐅᔪᓐᓇᙱᑦᑐᖅ ᓅᔪᐃᑦᑐᑎᑐᑦ ᐅᕝᕙᓘᓐᓃᑦ ᐆᒪᔪᑕᖃᙱᑦᑐᖅ ᓇᔪᕐᕕᖓ. ᑭᓯᐊᓂ ᓇᔪᕐᕕᒃ ᐊᐅᓚᐃᓐᓇᖅᑐᖅ, ᐳᑉᓚᔪᓂᒃ ᑕᑕᑦᑐᖅ. ᓂᕕᖓᔪᓕᐅᖅᑏᑦ ᐃᖅᑲᐅᒪᔾᔪᑎᒋᔭᖓ ᐅᕙᒻᓄᑦ ᐸᐅᙵᖅᓯᐅᕆᐊᖅᑐᖓ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᔨᒃᑲ ᑕᑯᔪᑦ ᐊᕚᓚᕿᐊᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓄᓇᐃᑦ ᑎᒍᒻᒥᔪᑦ ᐱᕈᖅᓯᐊᓂᒃ. ᐃᔨᒃᑲ ᐅᐃᕙᒃᑲ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑕᑯᔪᖓ ᐸᐅᕐᖓᓂᒃ. ᐃᔨᒃᑲ ᒪᑐᕙᒃᑲ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑕᑯᔪᖓ ᐸᐅᕐᖓᓂᒃ. ᐃᑉᐱᓐᓇᖅᑐᖃᖅᑐᖅ ᐃᓗᒻᓂ ᐊᐅᓚᓂᖓᓄᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐊᔾᔨᒌᙱᑦᑐᑦ ᑭᓗᖏ − ᖁᕕᐊᓇᖅᑐᖅ.

English

Hello, this is Asinnajaq, a member of the Curatorial team. I am from Inukjuak, Nunavik and have spent most of my time in Tiohtià:ke also known as Montreal, Quebec.

Our beautiful Inuit Nunaat is a landscape of movement and change. Over the seasons we witness the lands as they grow and melt, shifting from snowy whites to vibrant greens and rusty reds and browns. Qaulluaryuks compositions and stitching bring to this work a motion that transports me to the rising and falling of the foothills, the winding of a river. This work is a great reminder that the Inuit Nunangat can hardly be described as a still or lifeless place. Rather it is a place of constant motion, effervescing with life. The tapestries remind me of when I go berry picking, and my eyes only see the bushes and ground hugging plants. I open my eyes, and I see berries. I close my eyes, and I see berries. There is a feeling stirred up inside me by the motion and the patterns of the stitches – contentment.

W.3-1258

Bill NasogaluakW.3-1258, 2020

green serpentine

Collection of the artist

Inuktut

Atiga Jennifer Qupanuaq May, E8-2571, aglaqtunga makpiraaq.

Kisitchiun

Ativuut sangivailuktut

Uvagut taimannga kamagiliguvut

Inuit atkavuut kamagiyuatlu

Uvagut, Inuit, ilisimayuruut

Atikput qumnayuk sivulliit innaitlu

Ativuut tadjva naitut nukatpiraaluklu niviaqsiraqlu

Isumaliuqtuaq sivituyumik surraituq

Taamna pitqusiq sivituyumiktuaq

Pitqusiq taimaunga ilatkin

Isumatuyut sangiyuklu ilatkin

Munarilugu, tamaita piqpaqiapkin inuuyaq

Isuma taimaunga ilatkin kisiani

Malirutaksaq kisiani Inuit inuusiq

Maqaiqtuaq suuk

1941mi, atiqput allauyuat.

Asiin kiinaq ungavausigaa maqaiqtuatlu

Allauyuat atiq, taamna kisitchiunmik

Eskimo inuusiq Nalunaitkusigaa

Nikaittuq uqaqtuat?

Uqaqtunga atiq ilaksaqtuat takunaqtut

Maqaigaa qimmiq tukuyuat

Nangititchiyuat ilisakvik

Uvagut nutaraat aittugaa

Pingasukipiaq maqaigaa

Irniqput paniklu

Iglum iluani nakuyuamiq

Angiyumiq annaigaa

Sivulliqmi attai maqaigaa

Qangma nutaraq

Qanuq inuusiq?! Uqaqtugut

Tapqua governmentmi patchintuat

Uumayuaqtugut

Ikayuqtuaqtugut

English

My name is Jennifer Qupanuaq May, E8-2571, and this is my poem.

The Number

Our names are powerful beyond measure

A part of us that we continue to treasure

Inuit names foster respect and closeness

We, Inuit, have always known this

Named after our ancestors and elders

Our names were not based on genders

To ensure a long and healthy lifestyle

This custom has been around for awhile

A custom passed down from generation to generation

To ensure a strong foundation

By cherishing our loved one’s legacy

Their spirit was passed down to become our identity

This tradition was the Inuit way

We never imagined it would be taken away

In 1941, our names were replaced.

While our faces displaced

Not by different names, but by a number

Eskimo identification Tags

Good intentions they say?

I say name exemptions on display

We also experienced

Residential schools

And our children put out as offers

The sixties scoop

Our sons and our daughters

Put in homes that were seen as better

Imagine how much this upset her

First her name taken

And now her children

How is this humane?! We exclaim

To a government who chooses to blame

We coped

And hoped

But yet still saw our rights revoked

We never fought

We only sought

For justice that was never brought

Instead of a face to a name

We now had a number that we became

Inuit names, but never numbers, fostered respect and closeness

We, Inuit, have always known this.

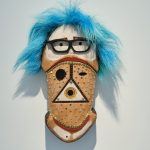

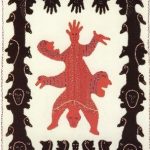

Arnaq & Angun (Handmade Dolls)

Ella Nasogak Nasogaluak-BrownArnaq & Angun (Handmade Dolls), 2015

handmade dolls of mixed media

Private Collection

Inuktut

Uvanga Kablusiak, apungma atinga Arlin Carpenter, Ikahukmun, amamamunga atinga Holly Nasogaluak Carpenter, tuktuyaktumun.

Tapqua kunuuyat sanayuat anaanangma Ella Nasogaluak Brown. Ella amamangma amung, anniviklu inuuyuat Tuktuuyaqtuuqmi. Ilakka Susie Ruben Nasogaluak Joe Nasogaluaklu Sr. Amamma ilisautdjiyaa miquqmiq. Ellam kunuuyat, savaktii asinnajaq takuyaa, uqaqtuaq mumiqtuut. Anaanangma amma uyuktuaq isumayunga kamagiyuaq asiin miquqa savaat.

Kunuuyat atuaksaqtaariyaa uvangamun WAG piliunaitut, uvanga qaita aimunmi. Uqaqtunga nutaraat ilisakvikmi Inuvialuit inuuyaq, amaamangma qaita kunuuyat asiin atugaa ilisautdjyaa nutakatmun. Kunuuyat ilisaqtuyuut tapqua malirutaksaq ilisimayuaq ilakkamun nutakatmunlu, nakuuyuq taamna ilisautdjiyaa surautat qangma inugiaktut tutqaanaittut. Anaanangma amaama miquqtuak kunuuyat, maniklu tapqua tan’ngit itiriaqtuqtiit Tuktuuyaqtuuqmi. Kunuuyat tadjvangatchiaqtuaq miquqtauak tan’ngitmun taamna savaaklu, suratuat savaak. Takunaqtuq miquqtuaq kunuuyat, nakuuyuq kamagilu – piqpagiyaa tamaita kiluk.

English

Uvanga Kablusiak, apungma atinga Arlin Carpenter, Ikahukmun, amamamunga atinga Holly Nasogaluak Carpenter, tuktuyaktumun.

These dolls were made by my nanuk Ella Nasogaluak Brown. Ella is my mom’s mom, and she was born and raised in Tuktoyaktuk. Her parents were Susie Ruben Nasogaluak and Joe Nasogaluak Sr. She was taught how to sew by her mother. Ella’s dolls, as co-curator asinnajaq noticed, are very dancey. My nanuk’s mom was a beautiful drum dancer and I feel like this must have influenced her and made its way into her art.

These dolls weren’t in the WAG’s collection, I brought them from home. I once spoke to a class of elementary school children about Inuvialuit culture, and my mom gave me these dolls to be used as a teaching tool. These dolls can provide valuable insight into how traditional skills were passed down from parents to young, and it’s great how these teaching tools can exist for a multitude of purposes. My nanuk’s mom made dolls as well, as a way to make money from settlers visiting Tuktoyaktuk. These dolls are a great example of how an object originally made for a more commercial purpose exists both as a sculpture, and textile based art. The amount of detail put into these dolls, especially at their scale, is incredible and very touching – I feel like you can see the care she put into each and every stitch.

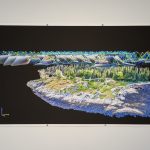

Hopedale Mission Buildings & Salmon Factory

Eldred AllenHopedale Mission Buildings & Salmon Factory, 2017

digital compositions on photo paper

Collection of the artist

Inuktut

Atelihai, una Asinnajaq, iligenguKataujuk Ukâlattiujuit iligenginnut. Inukjuangumiunguvunga Nunavimmi ammalu iniKaluasimavunga Tiohtià:ke-imi Kaujimajaummijuk imâk Montreal, Quebec.

Atautsik takuminattuk ilutsitâtitsisimajuk Inunnik ammalu Inuit ilikkusinginnik, ukuanguvut sanautet sivullivinivut sivullimi sanalautsimajangit ammalu atuKattasimajangit ullu tamât ulluk nânninganut. IsumakKutujovugut ammalu atugumaKattavugut nukkitinnik atuniKatsiatumik Kangatuinnak pigiaKaligutta. Tamannauluavuk Inuit atuKattagajattut sunatuinnanik ikajuniattunut. Atulluni ikittunik atuttausonik ammalu isumagijanginnik, Allen sakKititsijuk nutâmik takutsaujumik nunatsuanut Nunatsiavummi. KaujimattitaulaukKunga atjiliugigiamut nunanik atuttausongutillugu ullumiulittumut Kulaugajattunut. Ilinniasimavunga atugiamut tâpsuminga Kaujisagiamut ammalu sakKititsigiamut atjinguanik angijualummut inimmik nunatsuamik taikkutigona suliagijauKattajumut Allen-imut.

Tâkkutigona piusimit tigusilluni atjinguanik, asianottisilluni ammalu tautselugu katitsutaumajunik pijagettausimajumut Kagitaujammut ilillugit minguattaungângumagajattut nânningani. Ammalu tigusilluni tamânneluasiajunik mânnaluatsiak, sulijunik piKutinik ammalu iniujunut, sunatuinnauliaKisok ammalu iniutluni kinaup isumanga pinguavigisongujanganik.

English

Hello, this is Asinnajaq, a member of the Curatorial team. I am from Inukjuak, Nunavik and have spent most of my time in Tiohtià:ke also known as Montreal, Quebec.

One of the beautiful things that shaped Inuit and Inuit culture, are the tools that our ancestors invented and used day in and day out. We are ingenuitive, and want to use our precious energy as effectively as possible where needed. This is a reason that Inuit are very willing to adopt technologies that can be of service. Using a few useful gadgets and his wits, Allen brings a new perspective to the landscapes of Nunatsiavut. I was first made aware of photogrammetry as a tool to bring objects into the VR realm. I only learned that this tool could be used to survey and create an image of a large area of the landscape through the work of Allen.

Through the process of capturing the image, transferring and altering of data the final result of these digital photos becomes quite painterly in the end product. And in the way the capturing of a very real moment in time, very real objects and places, they become an abstraction and a space where one’s imagination can play.

In View of the Future

Tommy NuvaqirqIn View of the Future, 1985

stencil on paper, 29/50

Government of Nunavut Fine Art Collection, On long-term loan to the Winnipeg Art Gallery, 987.5.28

Inuktut

ᓂᑰᓪ ᓘᒃᖑᕗᖓ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓚᒃᑲ ᐃᒡᓗᓕᒐᖅᓯᒻᒦᖓᕐᓂᑰᕗᑦ, ᓄᓇᕗᑦ.

ᑖᒥ ᓄᕙᕿᒃ ᐃᓚᒋᔭᐅᒻᒪᑦ ᐊᒥᓱᓂᒃ ᓴᓇᙳᐋᖅᑎᐅᕙᒃᑐᓂᑦ ᑖᒃᑯᐊᓗ ᐃᖃᓇᐃᔭᕐᓗᑎᒃ ᐸᓐᓂᖅᑑᒥ. ᐃᓅᓚᐅᖅᓯᒪᓪᓗᓂ 1911-ᒥ, ᐱᕈᔅᓴᓚᐅᖅᓯᒪᓪᓗᓂ ᓅᓯᒪᒐᔪᓪᓗᓂ ᐊᐅᓪᓚᖅᓯᒪᕙᓪᓗᓂ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐊᖑᓇᓱᐊᖅᐸᓪᓗᓂ ᓴᖅᐱᓕᓐᓂᒃ ᐸᓐᓂᖅᑐᑉ ᖃᖏᑦᑐᖓᓂ. ᑕᒪᓐᓇ ᐃᒪᓂᐅᒻᒪᑦ ᑎᑭᐅᒪᓪᓗᓂ ᐸᓐᓂᖅᑐᒥᒃ ᑕᐅᕗᖓ ᐃᒪᐅᓂᖓᓄᑦ ᐅᑭᐅᖅᑕᖅᑐᒻᒥ ᐃᒪᕕᒻᒧᑦ. ᐊᒥᐊᖅᓯᒪᔪᓕᐅᕐᕕᒃ ᐸᓐᓂᖅᑐᒻᒥ ᒪᑐᐃᓚᐅᖅᓯᒪᒻᒪᑦ 1973-ᒥ, ᑕᒪᓐᓇᓗ ᐊᑑᑎᓕᓚᐅᒻᒪᑦ ᓄᕙᕿᒃ ᑭᒡᒐᖅᑐᐃᓕᓪᓗᓂ ᐊᔾᔨᒌᖏᑦᑐᓂᒃ ᖃᓄᐃᓕᐅᓂᐅᔪᓂᒃ ᐃᓅᓯᖓᓂ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓄᓇᓕᒃ ᐃᓗᐊᓂ ᐊᒥᐊᖅᓯᒪᔪᓕᐅᕝᕕᒋᓗᓂᐅᒃ ᐃᖃᓇᐃᔭᓪᓗᓂ. ᑖᓐᓇ ᓴᓇᓯᒪᔪᖅ, “ᑕᑯᓐᓈᓪᓗᒍ ᓯᕗᓂᒃᓴᖅ,” ᑭᒡᒐᖅᑐᐃᒻᒪᑦ ᖃᑦᓯᓐᓇᐅᒐᓗᐊᓂᒃ ᓴᓇᓯᒪᓂᐅᔪᓂᒃ, ᐃᒫᖑᑐᐃᓐᓇᕆᐊᖃᓪᓗᑎᒃ ᐃᓗᐊᓂ ᐸᓐᓂᖅᑐᑉ, ᐊᔾᔨᒌᖏᑦᑐᑖᐅᓗᑎᒃ ᓇᔪᒐᒻᒥᐅᑕᑦ ᖃᓄᐃᑦᑑᓂᖏᑦ. ᐱᑕᖃᕐᒪᑦ ᕿᔪᒻᒥᒃ ᖃᓇᖃᐅᑦᑐᓂᒃ ᐃᐅᕋᑉ−ᑲᓇᑕᒥ ᓴᓇᔭᐅᓱᑎᑐᑦ ᐃᓪᓗᑕᖃᐅᓪᓗᓂ, ᐃᓚᒋᔭᐅᓪᓗᓂ ᑐᔅᓯᐊᕐᕕᒃ, ᐃᓚᒋᔭᐅᖃᓯᐅᑎᓪᓗᑎᒃ ᑐᐱᐅᑰᔨᔪᑦ ᐱᖁᓯᒃᑯᑦ ᓴᓇᓯᒪᔪᑦ. ᐅᔾᔨᕆᓗᒋᑦ ᐅᐋᔭᖃᐅᑎᖃᒃᕕᑦ ᑕᒪᒃᑯᓇᓂ ᕿᔪᓐᓂᒃ ᖃᓇᖃᐅᑦᑐᑦ ᐃᒡᓗᖃᒃᑎᑦᑎᕕᐅᔪᓂ. ᐊᑕᐅᓯᖅ ᑖᒃᑯᓇᓂ ᐅᕐᕈᓯᒪᒻᒪᑦ, ᑕᒪᓐᓇ ᑕᐃᒪᐃᒍᑎᖃᑐᐃᓐᓇᕆᐊᓕᒃ ᐊᒃᓱᐋᓗᒃ ᓯᓚᕈᔫᖃᑦᑕᕐᓂᖓᓄᑦ ᐅᑭᐅᖅᑕᑦᑐᒻᒥ, ᐅᕝᕙᓗᓂᒃ ᖃᐅᔨᒍᑕᒍᓐᓇᑐᐃᓐᓇᕆᐊᓕᒃ ᓄᓇᐅᑉ ᖁᐊᖑᓂᖓᑕ ᐱᐅᒍᓐᓃᑉᐸᓪᓕᐊᓂᖓᓂᒃ. ᑕᑯᒐᔭᒻᒥᔭᑎᑦᑕᐅᖅ ᖃᔭᐃᑦ ᐃᓕᔭᐅᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᓄᓇᒧᑦ, ᐊᖏᔪᐋᓗᓗᑎᒃ, ᓄᑖᖑᓂᔅᓴᐃᑦ ᐅᒥᐊᑦ ᐃᑲᓗᒐᓲᒍᑕᐅᑐᓐᓇᕆᐊᓕᑦ ᐃᒪᕐᒥ. ᖄᖓᓂ ᖃᖅᑲᕋᓛᑉ, ᖁᓛᓂᑦ ᑕᑯᓗᒍ ᓄᓇᓕᒃ, ᖃᓕᕇᖑᒻᒪᑕ ᐅᔭᕋᐃᑦ. ᑖᓐᓇ ᐃᓄᒃᓲᕙ ᑐᑭᓯᑎᑦᑎᒍᑏ, “ᐃᓅᖃᑎᒋᑦ ᑕᕝᕙᓃᒻᒪᑖ,” ᐅᕝᕙᓗᓂᑦ ᑭᒡᒐᑦᑐᐃᒍᓐᓇᑉᐹ ᐊᓯᐋᓂᒃ ᑕᒫᓂ ᓄᓇᐅᓂᖓᓐᓃ? ᑕᑯᓐᓈᓪᓗᒍ ᓯᕗᓂᒃᓴᒥ ᑐᑭᖃᒃᐹ ᐱᓕᐋᖑᓂᖓᓃᒃ ᐱᕙᓪᓕᐊᑎᑕᐅᓂᖓᑖ ᐃᓗᐊᓂ ᐅᑭᐅᖅᑕᖅᑐᒻᒦ ᓄᓇᓕᒻᒦ, ᑭᓯᐊᓂ ᐊᐱᕆᔭᐅᓚᐅᖅᑖ “ᖃᓄᐃᓕᕙᓪᓕᐋᓂᐊᒻᒪᖔᑖ ᑕᒪᒃᑯᐊ ᐅᑭᐅᖅᑕᖅᑐᒻᒦ ᓄᓇᓖᑦ?” ᐃᓪᓗᓕᐅᓐᓂᖅ ᐅᑭᐅᖅᑕᖅᑐᒻᒥ ᐱᔭᐅᓲᖑᒻᒪᑦ ᐊᔾᔨᐅᖏᑦᑐᓂᒃ ᐱᓕᕆᓇᓱᐊᕆᐊᖃᓐᓂᒻᒥᒃ, ᑭᓯᐊᓂ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᑕᐅᓴᖏᓐᓃᑦᑐᓂ ᐊᕐᕌᒍᓂ ᐱᓕᕆᑦᑎᐊᕋᓱᐊᓪᓗᑎᒃ ᓇᐆᒃᑰᓱᖑᒻᒪᑕ ᐃᓅᓯᒻᒥᓐᓂ ᐃᓅᒍᒪᓪᓗᑎᒃ ᑕᒫᓂ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓚᒋᓗᒍ ᓄᓇ.

English

I’m Nicole Luke and my family is Chesterfield Inlet, Nunavut.

Tommy Nuvaqirq was one of the many artists who worked in Pangnirtung. Born in 1911, he grew up closely tied to the land, and hunting whales in the Cumberland Sound. This is the body of water which connects Pangnirtung to the open Arctic Ocean. The printshop in Pangnirtung only opened in 1973, which led to Nuvaqirq representing a variety of stages in his life, and community within his print work. This piece, “In View of the Future,” represents a few structures, possibly within Pangnirtung, with a contrast of dwelling types. There are wood framed Euro-Canadian style houses, one of them being a church, along with tent-like traditional structures. Notice the powerlines in the wood framed housing area. One of them has fallen over, this could be due to the extreme weather patterns of the arctic, or it could be a tell-tale sign of permafrost degradation. You can also see qajaqs placed on the land, with a larger,newer boat possibly fishing in the water. On the top of the hill, overlooking the community, are stacked rocks. Is this an Inukshuk saying, “people are here,” or could it represent something else beyond this landscape? In View of the Future signifies the stages of development within a small arctic community, but also asks us “what lies ahead for these arctic communities?” Construction in the arctic comes with very unique challenges, but Inuit for thousands of years have been strategically maneuvering their way of life to live on and with the land.

Jijuu Playing Bingo

Darcie BernhardtJijuu Playing Bingo, 2018

oil on canvas

Indigenous Art Centre, ID No. 501065

Inuktut

Uvanga Kablusiak, apungma atinga Arlin Carpenter, Ikahukmun, amamamunga atinga Holly Nasogaluak Carpenter, tuktuyaktumun.

Darciem piksaq itqaqtuami kamagilu: inuusivut, ingilraan, itiriaqtuqti, isumalu, tadvja. Naimayuaq taamna iksivavik.

Auyami 2018, aulayuami Inuvikmun Tuktuuyaqtuuqmunlu sivulliqmi inuinnaqmi. Aulaktunga savaakmilu. Qanuq isumayuami kamagiyunga – niqiyuami Inuit putuligaat, pisuktungalu itqaqtuaqmilu taamna nuna, kikturiat kiiyuat, uqaqtugut ilanaatlu takunaitat ingilraanimun. Saanganimun aulayuami, isumayuami itiriaqtuqtunga, asulu kamagiyuami. Takuyaga angakma savaak, aksaligmiq takuyaga Tuktuuyaqtuuq nuna kamagi ilatkamun. Takuyaga iluviqsivik amaukłuk, takuyagalu angaatdjuvik anaanama katitiqtuat. Takuyaga ililsakvik amamanga ilisaktuat, siniktunga atchangma igluum. Taamna piksaq itqautipkaqsagaa. Qaisuktunga takunaqtugunga taamna piksaq.

English

Uvanga Kablusiak, apungma atinga Arlin Carpenter, Ikahukmun, amamamunga atinga Holly Nasogaluak Carpenter, tuktuyaktumun.

Darcie’s paintings for me stir up many feelings and connotations : time spent, time passing, visiting, and nostalgia, being a few. I feel like I can smell this living room.

In summer of 2018, I went to Inuvik and Tuktoyaktuk for the first time in about 20 years. I was able to go because of an artist residency. This was a very emotional experience for me – I ate a lot of Inuit donuts, walked around a lot refamiliarizing myself with the place, got chewed up by mosquitos, and I was able to spend time with relatives I hadn’t seen in many years. During my time up north, I felt a strange mixture of being a guest, and experiencing a sense of belonging. My great- uncle showed me around his carving studio, drove me around tuk and showed me landmarks important to our family. I saw the graveyard where my great grandparents are buried, I saw the church where my nanuk was married. I saw the school where my mom teaches and I stayed at my great-aunt’s for the night. This painting brings up all those thoughts. I can’t look at it for too long without wanting to cry.

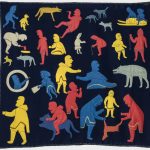

Large Feast on a Bed of Cardboard & Whale Hunt: I Think Everyone is Here

Megan Kyak-MonteithLarge Feast on a Bed of Cardboard & Whale Hunt: I Think Everyone is Here, 2019-2020

stop motion animation, paper, oil pastels, glass and oil paint

Collection of the artist

Inuktut

ᑯᕆᔅᑕ ᐅᓗᔪᒃ ᔭᕗᐊᑦᓯᑭᐅᕗᖓ ᐃᒡᓗᓕᒑᕐᒥᐅᑕᐅᔪᖓ ᐊᒻᒪ ᑲᖏᖅᖠᓂᕐᒥ, ᓄᓇᕗᑦ. ᐃᓚᒋᔭᐅᔪᖓ ᐊᐅᓚᑦᑎᔨᐅᔪᓂᒃ ᐆᒥᖓ ᐃᓄᐊ.

ᒦᒐᓐ ᖃᔮᖅ-ᒫᓐᑏᑦ ᐱᓕᕆᐊᖓᒍᑦ ᐃᓅᓯᕐᒥᓂ ᓴᖅᑭᑎᑦᑎᕙᒃᑐᖅ, ᐃᖅᑲᐅᒪᔭᖏᑦ ᑎᑎᕋᖅᐸᓪᓕᐊᓪᓗᓂᒋᑦ ᑎᑎᕋᐅᔭᒐᖓᒍᑦ. ᑕᒪᒃᑯᐊ ᐊᑭᓐᓇᒦᑦᑐᑦ ᐃᓅᙱᑦᑐᓄᑦ ᑎᑎᕋᐅᔭᒐᕐᓂᖅ ᐱᑕᖃᐅᕐᓂᕐᓴᐅᑎᓪᓗᒍ, ᒦᒐᓐ ᐃᓂᓕᐅᖅᐸᓪᓕᐊᔪᖅ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᑎᑎᕋᐅᔭᒐᕈᓯᖓᓂᒃ. ᓴᖅᑭᑎᑦᑎᕙᓪᓕᐊᓪᓗᓂ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐃᓅᓯᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᓴᓇᐅᒐᕆᕙᒃᑕᖏᓐᓂᒃ, ᒦᒐᓐ ᐃᑲᔪᖅᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᓴᖅᑭᑎᑦᑎᕙᓪᓕᐊᓂᕐᒥ ᐃᓱᒪᒋᔭᐅᓯᒪᔪᒥ ᖃᑯᖅᑕᒦᖢᓂ ᓯᓚᒻᒧ ᐃᑦᑐᐊᖅᑐᑐᐃᓐᓇᕐᓂᕐᒥᒃ ᒪᐅᖓ ᖃᓄᐃᓂᖓᓂᒃ ᐃᓅᓪᓗᓂ ᐅᓪᓗᒥ. ᓴᓂᖅᑯᑉᐸᓪᓕᐊᔪᓄᑦ, ᐅᔾᔨᕈᓱᓗᐊᕐᓇᙱᑦᑐᖅ ᒦᒐᓐ ᑎᑎᕋᐅᔭᒐᖏᑦ ᓴᙱᓂᖏᓐᓂᒃ. ᐊᑯᓂᐊᓗᒃ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐊᖑᓇᓱᖁᔭᐅᓚᐅᙱᒻᒪᑕ ᐊᕐᕕᖕᓂᒃ ᑭᓯᐊᓂᓕ ᐊᔪᕈᓐᓃᖅᑎᑕᐅᓵᓚᐅᕐᓯᒪᔪᑦ. ᑕᐅᑐᒃᖢᒋᑦ ᓄᓇᓖᑦ ᐱᓕᕆᔪᑦ ᑲᑐᔾᔨᓪᓗᑎᒃ ᐊᕐᕕᖕᒥ ᑕᕝᕙᓂ ᑕᕐᕆᔭᒐᕐᒥ ᐃᓱᒪᒋᔭᖃᕐᓇᖅᑐᖅ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐃᓚᐅᓂᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪ ᓄᓇᖃᑎᒌᖕᓂᖏᓐᓂᒃ.

ᑕᕝᕙᓂ ᑕᕐᕆᔭᒐᒃᓴᒥᑦ ᒪᕐᕉᖕᓂ ᓴᖅᑭᑎᑦᑎᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᒦᒐᓐ ᐊᑕᐅᓯᑦᑕᐃᓐᓇᕐᒥᒃ, ᐱᒻᒪᕆᐊᓂᖓᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪ ᐊᑐᒻᒪᕆᖕᓂᖓ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐊᑐᖃᑦᑕᖅᑕᖓᓂᒃ: ᓂᕿᖃᖃᑎᒌᖕᓂᖅ. ᐊᖑᓇᓱᖕᓂᖅ ᐊᖏᔪᐊᓗᖕᒥ ᐊᕐᕕᒃᒥᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᒪᒃᑕᖓᓂ ᓂᕆᓂᖅ ᐊᑕᐅᓯᑦᑕᐃᓐᓇᐅᕗᖅ. ᐊᔾᔨᒌᙱᑦᑑᑎᐅᓂᖏᑦ ᓂᕿᓂᒃ ᐱᖃᖅᑎᑦᑎᕙᖕᓂᕐᒥᒃ, ᓄᓇᓕᓕᒫᑦ ᐊᒻᒪ ᐃᓚᒌᓕᒫᓂᒃ ᐃᒃᐱᒍᓱᑉᓂᖃᕐᓇᖅᐳᖅ, ᑕᐃᒪᓐᓇᐃᑦᑐᒃᓴᐅᓪᓗᓂᓗ ᐅᓄᕐᑐᓄᑦ ᐃᓄᖕᓄᑦ. ᒪᒃᑕᐃᑦ ᐊᕕᒃᑐᖅᑕᐅᓪᓗᑎ ᑕᒧᐊᔭᐅᔪᓐᓇᕐᓯᓯᒪᓪᓗᑎᒃ ᐃᒃᐱᖕᓇᒻᒪᕆᒃᑐᖅ, ᐱᓗᐊᕐᑐᒥ ᐊᒡᒐᑯᓗᐃᑦ ᑎᒍᓯᒋᐊᖅᑎᓪᓗᒋᑦ ᑕᒧᐊᓂᐊᖅᑕᖏᓐᓂᒃ. ᓲᕐᓗᓂ ᐃᓚᒃᑲ ᑕᐅᑐᒃᑕᒃᑯ ᓂᕿᑐᖅᑐᑦ.

English

I am Krista Ulujuk Zawadski from Igluligaarjuk and Rankin Inlet, Nunavut. I am one of the co-curators of INUA.

A lot of Megan Kyak-Monteith’s work captures her own life, cataloging her memories through art. In a space that is dominated by non-Inuit art, Megan is making space for contemporary Inuit art. Bringing forward a contemporary flip of Inuit lives and Inuit art, Megan is helping pave the way to bring the gaze outside of the colonial white cube and into the what it means to be Inuk today. For the passers-by, you may not realize the power of imagery in Megan’s work. Up until relatively recently, Inuit were not allowed to hunt arviq, the bowhead whale. Seeing the community working together to harvest the arviq in the film is a visual statement of the power of Inuit sense of belonging and community.

In the films Megan shows two aspects of the same, important and fundamentally Inuk thing to do: sharing food. The harvest of the massive whale and the sharing of bite-size pieces of maktak is one and the same. The different scale of food sharing, the whole community and the whole family, resonates with me particularly, as it most likely does for many Inuit. The preparing of the maktak by cutting it into small cubes so that it is edible is palpable, especially when you see the little hands grab the cut pieces. It is as though I am watching my own family meal.

Migration

Joe TaliruniliMigration, 1965

stone, bone, gut, sinew

Winnipeg Art Gallery, Twomey Collection, with appreciation to the Province of Manitoba and Government of Canada, 1951.71

Inuktut

ᐁ, ᐊᓰᓐᓇᔮᖑᕗᖓ, ᐃᓚᒋᔭᐅᕗᖓ ᑲᒪᔨᐅᓂᕐᒥᒃ ᐱᓇᓱᖃᑎᒌᑦᑐᓄᑦ. ᐃᓄᑦᔪᐊᒥᐅᔭᐅᕗᖓ ᓄᓇᕕᒻᒥ ᑎᐆᑎᐊ:ᑮᒥ ᒪᓐᑐᔨᐊᖑᓂᕋᕐᑕᐅᕙᒻᒥᔪᒥ ᑯᐯᒃᒥ ᓄᓇᓯᒪᓂᕐᓴᐅᓱᖓᔪᖓ.

ᑖᒃᑯᐊ ᓴᓇᖕᖑᐊᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᐱᒫᕋᑦᓴᔭᐅᑦᓱᑎᒃ ᓴᓇᐅᒐᐅᕗᑦ. ᑖᒃᑯᐊ ᐱᓇᓱᑦᑕᐅᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᑕᑯᒋᐅᕈᑎᒋᓯᒪᕐᖂᐸᒃᑲ ᓯᓛᕐᓯᒪᔪᒥᒃ ᑮᓇᓕᐅᑦᓱᑎᒃ ᐃᓄᖕᖑᐊᓕᕕᓂᕐᓂᒃ. ᐅᕕᓂᖕᖑᐊᖓ ᑲᔪᖅ ᐊᑦᑐᓱᒍ ᓲᕐᓗ ᓂᕈᒥᑦᑐᖅ ᐃᓄᖕᖑᐊᒥᒃ ᓲᕐᓗ ᐊᓂᕐᓂᖃᒃᑫᔪᖅ. ᐅᕕᓂᖕᖑᐊᖓ ᐃᓱᒪᓇᕐᒥᔪᖅ ᐊᓄᕐᓯᐅᑐᕕᓂᖕᖑᐊᖑᒋᐊᖓ. ᐅᓂᒃᑲᐅᓰᑦ ᓄᑦᑎᓂᐅᓯᒪᔪᒥᒃ ᑕᓕᑐᓂᓕᐅᑉ ᐃᓅᓯᕐᒥᓂ ᐊᑑᑎᓯᒪᔭᒥᓂᒃ ᐊᑦᑐᐊᔨᒋᑦᓯᐊᒪᐅᒃ ᐅᑎᕐᑕᕕᒋᒍᓱᖃᑦᑕᓚᐅᔪᕙᖓᓗ ᐃᓄᒻᒪᕆᐅᓂᕐᓴᐅᓕᕐᓱᓂ. ᓱᓇᑐᐃᓐᓀᑦ ᐃᓅᓯᕐᒥ ᐊᕐᖁᓵᕐᑐᑦ ᐃᓚᖏᑕ ᐊᑦᑐᓚᕆᓲᕆᒻᒫᑎᒍᑦ.

ᐃᓚᒃᑲᓂᒃ ᐃᓚᖃᓱᖓ, ᖁᕕᐊᓱᖃᑎᖃᕐᐳᖓ ᐅᒥᐊᒃᑯᑦ ᓯᓚᒥ ᓂᕆᔭᕐᑐᖃᑎᖃᕆᐊᒥᒃ. ᑌᒃᑯᓇᓂ ᐅᓪᓗᓂ ᓄᓗᐊᓕᕆᒋᐊᕐᑐᒋᒥᒃ, ᑎᒻᒥᐊᓂᒃ ᑕᑯᓐᓇᐅᔮᕆᒥᒃ ᐅᕝᕙᓗᓐᓃᑦ ᐳᐃᔨᓐᓂᐊᕆᐊᒥᒃ, ᐃᒻᒪᖄᓗ ᐃᓚᖓᓂᒃ ᒥᕐᖁᓕᑦᑕᕆᐊᕆᐊᒥᒃ ᕿᒻᒥᓂᓪᓗ ᓂᕆᒃᑫᒋᐊᕐᑐᕆᐊᒥᒃ ᕿᑭᕐᑕᓃᑎᓪᓗᒋᑦ ᐊᐅᔭᒥ, ᕿᑭᕐᑕᒥ ᐸᖓᓕᑭᑕᕝᕕᒋᒍᓐᓇᑕᒥᓐᓂ, ᖃᑦᑕᓂᓪᓗ ᐃᕐᕋᕕᕕᓂᕐᑕᓕᓐᓂᒃ ᕿᒻᒥᓄᑦ ᓂᕆᒃᑲᐅᑎᖃᕆᐊᕐᑐᕆᐊᒥᒃ ᐊᓂᕐᕋᑎᓐᓄᑦ ᐃᖏᕐᕋᓕᕐᓱᑕ. ᓄᑦᑎᓂᖃᕐᓂᖅ ᐱᓇᓱᓕᕋᒃᑯ ᐃᕐᖃᐅᒪᓱᖑᕗᖓ ᐅᒥᐊᒥ ᐅᓯᑦᑑᑎᐅᖃᑦᑕᓯᒪᒐᑦᑕ ᓄᐊᑯᓗᒃᑲᓗ ᐃᓚᒃᑲᓗ. ᓂᕆᓇᓱᑦᓱᑕ ᑕᑯᓐᓇᐅᔮᕐᓱᑕᓗ ᐃᒪᐅᓪᓗ ᓯᑦᔭᐅᓗ ᑕᑯᔭᑦᓴᖁᑎᖏᓐᓂᒃ.

English

Hello, this is Asinnajaq, a member of the Curatorial team. I am from Inukjuak, Nunavik and have spent most of my time in Tiohtià:ke also known as Montreal, Quebec.

This is a completely legendary piece of artwork. I think that this work is one of the first carvings that I saw in person with tanned skin used in it. The brown of the skin brings a warm texture to the carving that brings a spark of life to the work. And the skin can hold a shape making it feel like maybe wind is being blown into it. The story of the migration is one very personal to Talitunili’s life experiences, and he visited this topic constantly in the later years of his lifetime. Some things really leave a mark on you.

With my family, we love going out on our boat for a picnic. A day where we check the nets, look at birds and chase a seal, maybe get some urchins and feed the dogs on their summer island where they run free, getting buckets of the guts from our days catch on our way home. This Migration work reminds me of being stuffed in the boat with my nieces and family. Snacking and observing what the water and shores have to show us.

Neutralizer

Ningiukulu TeeveeNeutralizer, 2015

stonecut on paper, 27/50

Winnipeg Art Gallery, Acquired with funds from the Estate of Mr. and Mrs. Bernard Naylor, funds administered by The Winnipeg Foundation, 2017-155

Inuktut

ᐊᐃᖓᐃ, ᓇᐸᑦᓯ ᕘᓪᒎᔪᖓ, ᐃᖃᓗᐃᑦ, ᓄᓇᕗᒻᒥ. ᑐᓗᒐᐃᑦ ᐱᙳᐊᖅᑎᓪᓗᒋᑦ ᑕᐅᑐᓚᐅᖅᓯᒪᕕᒌᑦ? ᑕᐅᑐᓐᓂᑰᒍᕕᑦ ᐅᑉᐱᓇᖅᑯᖅ ᑖᒃᑯᐊ ᑯᐊᕕᑦ (ᑎᒻᒥᐊᖑᔪᑦ ᑐᓗᒐᐃᑦ ᐃᓚᒋᓪᓗᓂᒋᑦ), ᓯᓚᑐᓂᖅᐹᖑᖃᑕᐅᔪᑦ ᑎᒻᒥᐊᓂᒃ ᓄᓇᕐᔪᐊᕐᒥᑦ. ᖃᐅᔨᒪᒻᒥᔪᑎᑦ ᐸᕝᕕᓴᖃᑦᑕᕐᓂᖏᑦ ᖃᐅᔨᒪᔭᐅᑦᓯᐊᖅᑐᑦ. ᑕᕝᕙᓂ, ᓂᖏᐅᑯᓗ ᑏᕕ ᑕᑯᑦᓴᐅᑎᑦᓯᔪᖅ ᑐᓗᒐᕐᒥᑦ ᐊᑐᖅᑐᓂ ᑭᒻᒥᑯᑖᓕᒻᒥ ᐃᓯᒐᐅᔭᕐᒥᑦ, ᓇᖏᖅᓯᒪᓪᓗᓂ ᐊᐅᐸᖅᑐᒥ ᐊᑭᓐᓇᖃᖅᑐᒥ. ᑕᐅᑐᐃᙳᐊᕐᓂᐅᔪᖅ ᑕᑯᑦᓴᐅᑦᓯᐊᖅᑐᖅ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐱᙳᐊᕐᓇᖅᓱᓂ ᑕᑯᑦᓴᐅᑎᑦᓯᔪᖅ ᓱᕈᓯᕐᒥᑦ ᐱᙳᐊᖅᑐᒥ ᐊᓈᓇᖓᑕ ᐊᓐᓄᕌᒃᑯᕕᖓᓂ, ᐊᑐᖅᓱᓂ ᐊᖏᒋᓗᐊᖅᑕᒥᓂᒃ ᑭᒻᒥᑯᑖᓐᓂ ᐃᓯᒐᐅᔮᓐᓂᒃ.

ᐊᔾᔨᙳᐊᖅ ᖁᕕᐊᓇᖅᑐᖅ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑕᑯᔪᒥᓇᖅᑐᖅ, ᑕᑯᑦᓴᐅᑎᑦᓯᑐᐃᓐᓇᖅᓱᓂ ᑐᓗᒐᐅᑉ ᓂᐅᖓᓂ ᑕᐅᑐᙳᐊᓕᖅᑕᕋ ᑐᓗᒐᖅ ᓈᑦᑐᐊᓘᓪᓗᓂ, ᐃᓴᕈᖏᑦ ᐃᓯᕕᓯᒪᓪᓗᑎᒃ ᐅᕐᕈᔾᔭᐃᖅᓱᓂ ᐊᑐᖅᓯᓐᓈᑦ ᖃᑯᖅᑕᒥ ᐅᔭᒥᒥ ᐅᕝᕙᓘᓐᓃᑦ ᓴᐸᖓᓕᒻᒥᒃ ᐅᔭᒥᒥ, ᐊᓐᓄᕌᖏᓐᓄᑦ ᐊᑕᖃᓯᐅᑎᔪᑦ. ᑎᑎᖅᑐᒐᖅᑎᐅᔪᖅ ᐊᔪᙱᑦᓯᐊᖅᑐᖅ ᖃᐅᑕᒫᖅᓯᐅᑎᓂᒃ ᓴᖅᑮᒍᓐᓇᖅᓱᓂ ᐅᑭᐅᖅᑕᖅᑐᒥ ᐃᓅᓯᕆᔭᐅᔪᓂᒃ ᑲᑎᖅᓱᖅᓱᓂᒋᑦ ᐃᔪᓐᓇᖅᑐᓂᑦ ᐃᓄᓐᓄᑦ ᑎᑎᖅᑐᒐᐅᔭᖅᑕᒥᓂᒃ.

ᑐᓗᒐᐃᑦ ᖃᖓᑕᖃᑦᑕᖏᑉᐸᑕ ᐊᓄᕆᒧᓪᓗ ᑎᑦᑕᐅᕈᓘᔭᖃᑦᑕᖅᓱᑎᒃ ᑕᐸᓱᑦᑐᑎᓗ ᕿᒻᒥᓂᑦ ᐱᑐᑦᓯᒪᔪᓂᑦ, ᐱᙳᐊᕆᐊᖅᑐᕋᔭᖅᑳ ᐊᓐᓄᕌᒃᑯᕕᑦᑎᓐᓂ? ᖃᐅᔨᒪᔪᒍᑦ ᑏᕕ ᖃᓄᖅ ᑭᐅᓯᒪᒻᒪᖔᖅ, ᖁᕕᐊᓱᑉᐳᒍᑦ ᐅᕙᑦᑎᓐᓄᑦ ᑕᑯᔭᐅᑎᒍᓐᓇᓚᐅᕐᖓᒍᑦ. ᐊᒥᓱᓄᑦ ᐅᖃᕐᓗᑕ, ᐃᓄᒋᐊᓗᐊᙱᑦᑐᑦ ᐅᖃᕈᓐᓇᖅᑐᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑐᑭᓯᐅᒪᔪᑦ ᐃᓄᒃᑎᑐᑦ. ᑕᐃᒪᐃᒻᒪᑦ, ᑎᑎᖅᑐᒐᐅᔭᖅᑏᑦ ᓂᖏᐅᑯᓗ ᑏᕕᑎᑐᑦ ᐱᒻᒪᕆᐅᕗᑦ ᓴᖅᑮᓂᕐᒥᑦ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐃᓱᒪᒋᔭᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑕᐅᑐᑦᑕᒥᒍᑦ, ᐊᒥᓱᕐᔪᐊᕌᓗᐃᑦ ᐊᓯᐅᔨᔭᐅᒍᓐᓇᖅᑎᓪᓗᒋᑦ ᑐᑭᓕᐅᖅᑕᐅᓂᒃᑯᑦ, ᑏᕕ ᓴᖅᑮᕗᖅ ᐊᔾᔨᙳᐊᓂᑦ ᑲᓲᒪᑎᑦᓯᔪᒥᒃ ᐃᓕᖅᑯᓯᕐᓄᑦ, ᓴᓇᑦᓯᐊᕐᓂᒃᑯᑦ.

English

Hi, I’m Napatsi Folger, from Iqaluit, Nunavut. Have you ever watched ravens play? If you have then it’s easy to believe that Corvids (the family of birds that ravens belong to), are some of the most intelligent birds on the planet. You also know that their reputation for mischief is definitely well-earned. In this print, Ningiukulu Teevee shows a raven donning a high-heeled shoe, standing out stark against a bright red background. The imagery is vivid and playful and calls to mind a young child at play in their mother’s closet, teetering dangerously in her too-big high-heels.

The image is fun and delightful, and though she only depicts the leg of the bird I can’t help but finish the scene in my head of a raven tripping clumsily, with wings out to balance while wearing an overlarge set of pearls or beaded necklace, to complete the outfit. The artist has an acute ability to take ordinary scenes of everyday northern life and combine them with refreshingly hilarious Inuit humour in so much of her work.

If ravens weren’t relegated to gliding and falling on pockets of wind and teasing chained up dogs, would they come and play in our closets? We know what Teevee thinks the answer is, and we are so glad she shared it with us. Globally speaking, few people can speak and understand Inuktitut. As such, artists like Ningiukulu Teevee are essential for conveying Inuit ideas and perspective, when so much can be lost in translation, Teevee creates images that transverse the bridge between cultures, with light-hearted creativity.

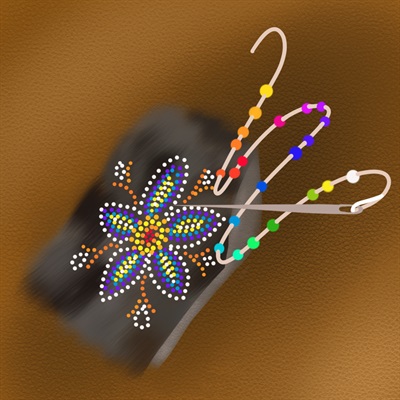

Our Flourishing Culture

Maata KyakOur Flourishing Culture, 2020

silk, embroidery lace, dyed sealskin, beds, pearls

Collection of the artist

Inuktut

ᑯᕆᔅᑕ ᐅᓗᔪᒃ ᔭᕗᐊᑦᓯᑭᐅᕗᖓ ᐃᒡᓗᓕᒑᕐᒥᐅᑕᐅᔪᖓ ᐊᒻᒪ ᑲᖏᖅᖠᓂᕐᒥ, ᓄᓇᕗᑦ. ᐃᓚᒋᔭᐅᔪᖓ ᐊᐅᓚᑦᑎᔨᐅᔪᓂᒃ ᐆᒥᖓ ᐃᓄᐊ.

ᑖᒃᑯᐊ ᐊᐅᓚᑦᑎᓂᕐᒧᑦ ᐱᓕᕆᖃᑎᒌᑦ ᓯᕗᓪᓕᖅᐹᒥᒃ ᐅᐸᓚᐅᕐᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᒫᑕᒥ ᑲᒪᒋᔭᖃᕈᒪᔭᕆᐊᒃᓴᖓᓂᒃ ᐆᒧᖓ ᐃᓄᐊ, ᖃᐅᔨᒪᓚᐅᕋᑦᑕ ᐱᓕᕆᐊᖓ ᐱᐅᒻᒪᕆᖕᓂᐊᕐᑐᖅ. ᐊᐱᕆᓚᐅᕋᑦᑎᒍᑦ ᐃᓱᒪᓕᐅᖁᓪᓗᑎᒍᑦ ᖃᓄᖅ ᓴᖅᑭᔮᕈᓯᖃᕐᓂᐊᕆᐊᒃᓴᑦᑎᓐᓂᒃ ᐆᒧᖓ ᐱᓕᕆᐊᑦᑎᓐᓄ, ᓯᕗᒧᒃᐸᓪᓕᐊᓂᖅ ᐊᑕᐅᑦᑎᒃᑯᑦ ᐃᓅᓪᓗᑕ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑐᑭᓕᐅᕆᓗᒍ ᒪᐅᓇ ᐊᑐᕈᓐᓇᕐᑐᓂᒃ ᓴᓇᐅᒐᓕᐊᑎᒍᑦ. ᐃᓱᒪᒋᓪᓗ ᖃᓄᑐᐃᓐᓇᖅ ᓴᓇᐅᒐᓕᐅᕈᓐᓇᕐᓂᖓᓂᒃ, ᐅᕙᑦᑎᓐᓄ ᖃᐃᒃᑲᓐᓂᓕᓚᐅᕐᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᓇᒃᓴᖅᖢᓂ ᑕᐃᔭᖓᓂ ᐱᕙᓪᓕᐊᓂᖓ ᐃᓕᖅᑯᓯᕗᑦ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓱᒪᔪᖓ ᑖᓐᓇ ᓴᖅᑭᑎᑦᑎᓯᒪᓂᖓᓂᒃ ᐆᒪ ᐃᓄᐊ ᐱᔾᔪᑎᒋᔭᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᓇᐅᒃᑯᕈᓘᔭᖅ.

ᐊᒪᐅᑎ ᓇᓗᓇᐃᕐᓯᒍᑎᐅᔪᖅ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐋᖅᑭᒃᓱᖅᓯᒪᑦᑎᐊᖅᖢᓂ ᐃᓄᖕᒧᑦ ᓴᓇᐅᒐᐅᓂᖓ, ᐊᓐᓄᕌᖅ ᐊᑐᖃᑦᑕᖅᑕᕗᑦ ᕿᑐᕐᖓᑦᑎᓐᓂᒃ ᐊᒫᕈᑎᐅᕙᒃᖢᑎᒃ ᐊᒻᒪ ᓴᐳᑎᓯᒪᒍᑎᒋᓪᓗᑎᒍᑦ. ᐅᓇ ᐊᒪᐅᑎ ᓴᖅᑭᔮᖅᑎᑦᑎᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᐃᓄᖕᓄᑦ ᐊᒃᑐᐊᒐᓚᒃᑐᓂᒃ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓚᒋᔭᐅᓂᖏᓐᓄᑦ ᑭᖑᕚᕇᖕᓂᒃᑯᑦ. ᐊᓈᓇᐅᔪᖅ ᐊᒫᖃᑦᑕᕐᑐᖅ ᕿᑐᕐᖓᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᐃᕐᖑᑕᖏᓐᓂᓪᓘᓐᓃᑦ ᐊᒪᐅᑎᖓᓄᑦ. ᑭᓇᑐᐃᓐᓇᕐᑕᐅᖅ ᐊᒫᕈᓐᓇᕐᒥᔪᖅ ᓄᑲᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᐅᕝᕙᓘᓐᓃᑦ ᐊᒫᕐᑐᐊᕐᓗᓂ ᐊᓯᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᐊᒪᐅᑎᖓᓂᒃ. ᑭᓇᑐᐃᓐᓇᖅ ᐊᒪᐅᑎᒥ ᐊᑐᖅᑐᖅ ᐊᒃᑐᐊᓂᖃᕐᑐᖅ ᐃᓅᓯᕆᔾᔪᓯᑦᑎᓐᓄᑦ ᐱᒻᒪᕆᐊᓗᒃᑯᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓱᒪᒋᔭᖃᑦᑎᐊᕐᓂᒃᑯᑦ.

ᖃᓄᐃᓕᖓᓯᒪᓂᖓ ᐱᕈᕐᓯᐊᙳᐊᖅ ᕿᓯᖕᒥ ᓴᓇᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᓴᖅᑭᑎᑦᑎᓯᒪᒋᕗᑦ ᐃᑳᕐᓂᕐᒥ ᐊᓯᐊᓄᑦ, ᐃᒪᓐᓇ ᕿᓰᑦ ᓴᖅᑭᑎᑦᑎᓯᒪᓂᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐃᓅᓯᖏᓐᓄᑦ ᐊᔾᔨᒌᙱᕈᓘᔭᕐᑐᒃᑯᑦ. ᒪᑯᓇᙵᑦ ᓂᕿᓂᒃ ᓇᑦᑎᕐᓂᙶᖅᑐᓂᒃ ᐅᕝᕙᓘᓐᓃᑦ ᐊᓐᓄᕌᖃᖅᐸᒃᖢᑕ ᕿᓯᖏᓐᓂᒃ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐅᓂᒃᑳᖅᑐᐊᒃᑯᑦ ᓇᑦᑏᑦ ᐅᖃᐅᓯᐅᖃᑦᑕᕐᓂᖏᑦ ᑕᐃᒪᓕ ᐊᑦᑐᐃᒍᑎᒋᕙᕗᑦ ᐃᑳᕈᑎᒋᓯᒪᓂᕐᒥ ᐊᒻᒪ ᓄᓇᓄᑦ ᓇᓗᓇᐃᒃᑯᑎᒃᑰᕐᓯᒪᓂᕐᒥᒃ.

ᐊᒪᐅᑎ ᓴᖅᑭᔮᕐᓂᖓ ᓇᓗᓇᙱᔾᔪᑎᐅᔪᖅ ᐃᓅᓪᓗᑕ ᐃᓕᖅᑯᓯᕆᔭᕗᑦ ᓱᓕ ᑕᕝᕙᐅᓂᖓᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪ ᐊᑐᖅᑕᐅᒻᒪᕆᖕᓂᖓᓂᒃ. ᓄᓇᕗᑦ ᑭᓱᖃᐅᑦᑎᐊᕐᒪ ᐃᒪᓐᓇᐅᙱᑦᑐᖅ ᐅᑭᐅᕐᑕᖅᑐᖅ ᐃᓱᒪᒋᔭᐅᓕᕌᖓᑦ ᑭᓱᖃᕋᓱᒋᔭᐅᙱᑦᑎᐊᖅᖢᓂ. ᐆᒪᓂᖃᑦᑎᐊᕐᑐᖅ, ᑕᕐᓴᖃᐅᑦᑎᐊᖅᖢᓂᓗ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑕᒫᓂ ᓄᓇᖃᖅᑐᓂ ᑐᑭᖃᕆᔭᐅᑦᑎᐊᖅᖢᓂ. ᒫᑕᐅᑉ ᓴᓇᐅᒐᖓ ᐱᕙᓪᓕᐊᓂᖓ ᐃᓕᖅᑯᓯᕗᑦ ᓴᖅᑭᑎᑦᑎᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᐅᕙᑦᑎᓐᓄᑦ ᐊᑐᒐᒃᓴᐅᔪᒃᑯᑦ ᓴᓇᐅᒐᒃᑯᑦ.

English

I am Krista Ulujuk Zawadski from Igluligaarjuk and Rankin Inlet, Nunavut. I am one of the co-curators of INUA.

When the curatorial team first approached Maata about commissioning a piece for INUA, we knew her work would be breath taking. We asked her to envision our theme, moving forward together as Inuit, and to translate that into wearable art. Given full autonomy to create a piece of art, she came back to us with a piece she calls Our Flourishing Culture, and I feel it encapsulates elements of INUA in many ways.

The amauti itself is an iconic and ingenious Inuit design, a garment we wear to carry and protect our children. The amauti represents Inuit relations, as well as belonging to multi generations. A mother might carry her children or her grandchildren in her amauti. A person might carry her siblings or young friends in her amauti. Whoever wears an Amauti is connected to our ways of living in an important and intimate way.

The intricate detail of the sealskin flowers adds another element of crossing borders, where the sealskin represents Inuit livelihoods in many ways. From the food seals bring to us or the clothing we wear from their skins, and the role seals have in our stories, the seal connects us across seas and borders.

The amauti makes a strong visual statement that our Inuit culture is vibrant and strong. Our homeland is not as bleak and bare as one might assume when they think of the arctic. It is actually full of life, full of colour and full of meaning for those who live there. Maata’s Our Flourishing Culture shows us that in her wearable art.

Arkhticos is Dreaming

Jessie KleemannArkhticos is Dreaming, 2016-2019

poem printed on nylon fabric

Collection of the artist

Inuktut translation coming soon

Hello, my name is Emily Laurent Henderson and I am an Inuk writer based in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. My family comes from Greenland, close to where poet and artist Jessie Kleemann hails from.

The first thing I notice about Jessie Kleemann’s Arkhticós is dreaming is the smell of it, as though her words have been transformed into a slow fungal and algae growth low to the ground or gathered around the shorelines. Cycling between growth and decay, and the growth that springs from decay, Kleemann paints a vivid, earthy picture of her homeland, Kalaallit Nunanat, better known as Greenland. Even to a reader that does not understand Kalaallisut, it is easy to read the verses at the pace one might breathe in the cold, salty air she so vividly invokes. You could almost walk with her as she takes you on a timeless journey through cold, moss, and seawater, shielding our eyes from snowblindness as we listen in for the song of a whale far off in the distance.

The poem is tied to Kleemann’s 2019 performance Arkhticós doloros, which was performed on the Greenland ice sheet. Using her body to engage with the ice and air that surrounded her, Kleemann comments on the political role played by ice at a moment shaped by unprecedented ice melt. In this gallery space, the poem has been suspended from the wall at an astonishing height of three storeys. Look upwards – what can you make out at the very top of the wall hanging? What can you see? In this cavern of the gallery space, Kleemann’s work almost asks us all to gaze as far as we can see, as though we ourselves were situated on the ice sheet with her, looking as far into the sky and the horizon as we could.

Ajjigiingiluktaaqugut (We Are All Different)

Lindsay McIntyreAjjigiingiluktaaqugut (We Are All Different), 2020

animation on S16mm to digital video, stereo sound, mixed media

Collection of the artist

Inuktut

ᐊᑎᕋ ᔨᓕᓐ, ᓂᓐ ᓄᓇᑦᓯᐊᕗᒻᒥᐅᑕᐅᓪᓚᕆᒃᑐᖓ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓄᓇᖃᖅᑳᖅᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᐊᐅᓚᑕᐅᙱᑉᓗᑎᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓕᑕᕆᔭᐅᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᐃᐊᒑᖕᑯᐃᓐ ᓄᓇᓕᒐ, ᖃᐅᔨᒪᔭᐅᔪᖅ ᐊᑐᕙ ᐋᓐᑎᐅᕆᔪ.

ᖃᓄᖅ ᑐᑭᖃᖅᐸ ᐃᓅᓗᓂ? ᖃᓄᖅ ᐃᓅᓗᓂ ᐊᓯᙳᖅᓯᒪᕙ ᑕᐃᒪᖓᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓇᔪᕐᕕᒻᒥ? ᑭᐊ ᓇᒻᒥᓂᕆᕙᐅᒃ? ᑭᓇ ᐃᓱᒪᒃᓴᖅᓯᐅᕈᓐᓇᙱᓚᖅ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓱᒪᒃᓴᖅᓯᐅᕈᓐᓇᖅᑐᑦ?

ᑕᑯᓐᓇᕐᓂᖓ, ᐅᕙᒻᓄᑦ, ᐊᑲᐅᓈᕈᓐᓇᕐᓗᓂ ᑭᓯᐊᓂ ᐊᑲᐅᓈᖅᑐᒃᑯᑦ ᑕᑯᑎᑦᑎᔪᖅ ᐃᖏᕐᕋᔪᒪᓂᖓᓄᑦ ᖃᓄᐃᑦᑐᒥᒃ − ᖃᓄᐃᓕᐅᖅᑕᐅᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᖃᐅᔨᒪᔭᐅᔪᑦ ᐃᓄᖕᓂᑦ ᖃᓄᐃᓐᓂᕆᔭᖏᓐᓄᑦ.